Ownership will consolidate driven by capital intensity and scale

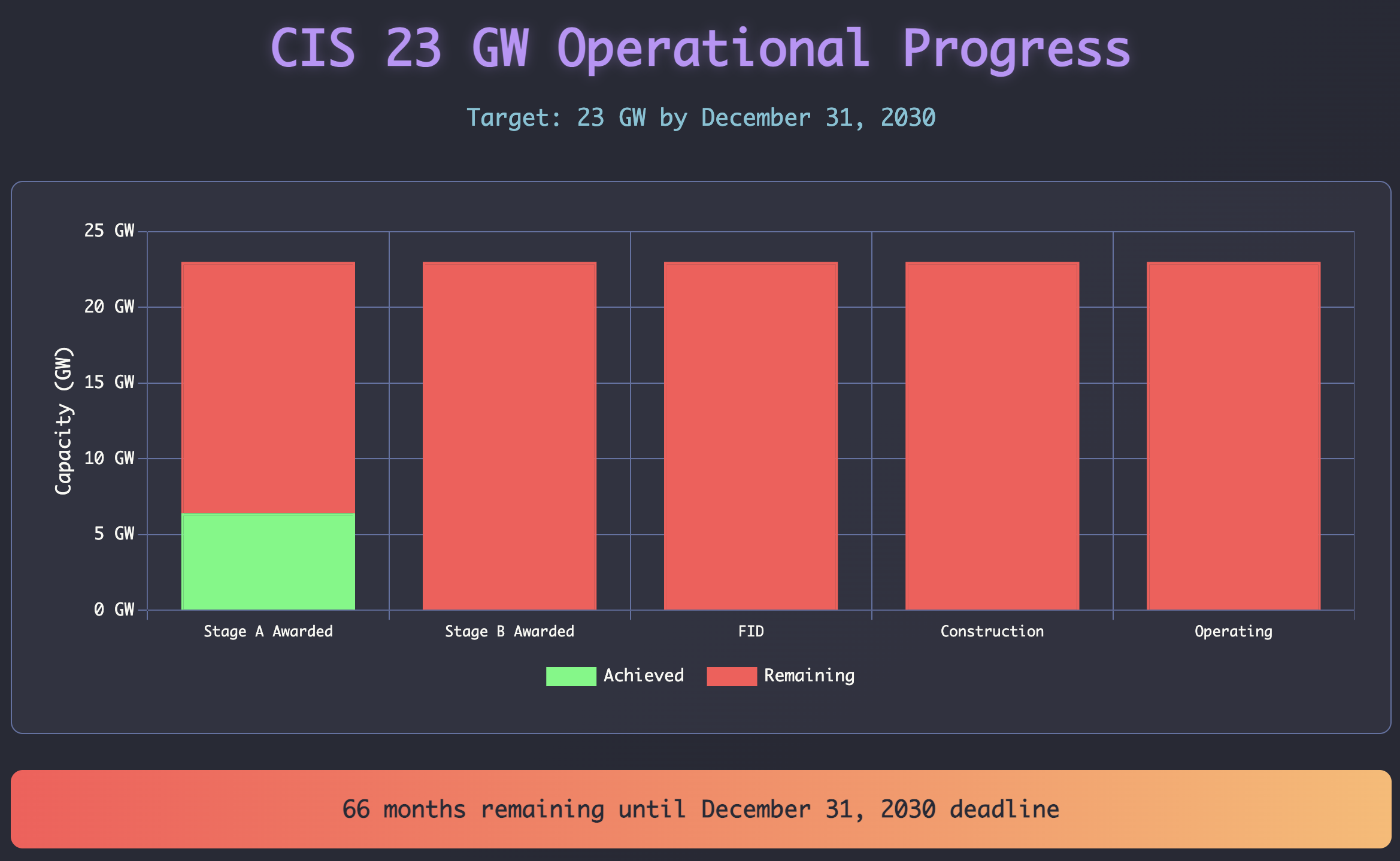

As discussed below over the next 66 months we are building 23 GW of wind and solar, of which not 1 MW has started construction. There is sufficient policy certainty its not an excuse. Although the technical challenges are the issues we all focus on most of the time this now looks more at the financing challenge.

23 GW of wind and solar is roughly A$75 bn of investment quite similar to the QLD LNG build a decade ago. Financing that $75 bn went relatively easily but I expect the wind and solar investment to be much harder. The reasons are that the LNG had relatively few owners, and relatively few projects in comparison to wind and solar. In Australia there are more than 60 owners of existing wind and solar and still more new players getting into the game. So there are many, many financing transactions to be done. Does this result in lower productivity? Maybe maybe not.

I expect the number of owners to steadily reduce and the ownership to consolidate over the next five years. The reasons for this are: (1) individual projects are getting larger, its $3 bn to finance a 1 GW wind farm as opposed to $600 m to finance a 200 MW one, there are just fewer businesses around that have that much capital access (2) bigger portfolios will in general have a lower cost of capital, not just from the portfolio effect but also from the technical expertise. BHP can get capital more easily than your local fish and chips shop, (3) Porter’s supplier bargaining power, you can buy your panels, inverters and turbines cheaper with big and steady orders and when you sit down to sell to AGL or Orgin you hold better cards as good or bad as theirs. (4) Its what happens in every industry.

Still this broad trend probably wont happen in time to ensure the success of finding $75 bn over the next 3 years. It’s something to keep an eye on. Of course there are large numbers of projects in the CIS queue and every one of them will have to have a credible source of finance identified so maybe I’m overthinking the problem, but for me its still of interest.

Surveying the field

It always seems like we do a lot of waiting in the analysis business. Sometimes, like now, the outlook in a few years time seems relatively clear, but in the short term it looks like nothing is happening.

I am working to the following assumptions.

The current Federal Govt will be in place long enough to award all the CIS contracts to be awarded as per the original November 2023 announcement.

Eraring and Yallourn will be closed by 2030 almost certainly by the end of 2028. Gladstone should be closed by the end of 2030 but the QLD Govt probably has a different view.

Energy Connect, Humelink, Orana REZ, Western Renewables Link will definitely be operating by 2030. VNI West will either be operational or well under construction. Although I can’t be certain about the New England REZ it still seems almost certain to be well under construction.

Other smaller pieces of transmission infrastructure will be operating;

At least 1 million houses will have batteries and residential solar penetration will be closer to 50% than 40%. There will also be lots of commercial, not utility, commercial batteries, although how much is a matter for discussion.

Less certainly there may be a couple of GW of offshore wind in Victoria

CIS

Two things have always been certain about the CIS. First the projects would need transmission and second that getting 23 GW of wind and solar going by 2030 was a big ask. Here is where the ITK dashboard sits. Never mind building, the projects have yet to get stage B awarded.

With reason even big solar farms can be constructed and made largely operational in say 30 months from the time construction preparation actually starts. Other than perhaps accommodation camps generally not too much in the way of road or port works is required. Nor are cranes needed. Productivity in post digging has continued to increase.

As we all know wind farm construction requires much more preparation and expertise. Road widening, cranes and crane operators, lots of transport. Nevertheless if well done a wind farm can be built and more or less fully commissioned in three years using Golden Plains Stage A as an example. On average though there often seem to be delays with wind farm commissioning so I’m going to allow 40 months.

Making a further assumption in line with Federal CIS tender 1 Stage A awards that roughly 40% or 9-10 GW of the 23 GW of VRE will be solar and about 13 GW will be wind. Then all of the wind needs to start construction by say September 2027 and the Solar by the end of 2028.

Obviously it can’t all be built at once so some will need to start well before those dates.

When we look at this from a financing perspective as discussed below it means that around $50 bn of debt needs to be arranged just for the wind and solar over the next 3 years.

Transmission 23 GW of Augmentation by 2030

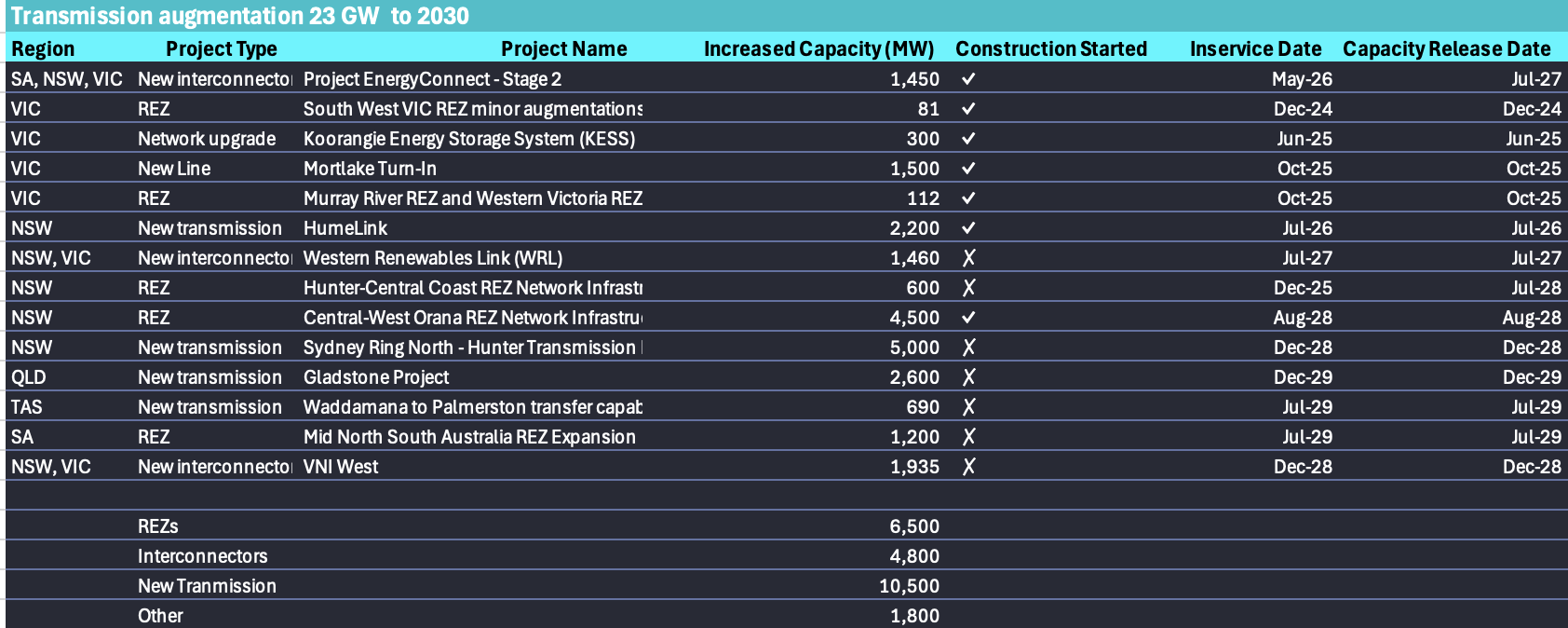

As it has been for years there is no way that 23 GW of wind and solar can be added to the system without more transmission. I used AEMO’s transmission augmentation page to put together a summary of what’s supposed to be built by 2030. Transmission augmentation is complicated in trying to make sense of what is needed to allow 23 GW of CIS capacity. Nevertheless this is the summary. By coincidence the transmission augmentation GW total equals the CIS new wind and solar total.

Playing with bigger pieces

ITK thinks that as the pace and scale of decarbonisation grows in Australia the market will consolidate. That’s because at least at the bulk energy but also for BESS the size of individual projects is increasing and the number of market participants who can afford it is reducing.

The CIS is a case in point. Notwithstanding that not one project from tender 1 (the first bulk energy tender) has so far progressed to FID it’s noticeable that the average size of the wind projects was over 500 MW and solar 229 MW. In addition virtually every solar project done these days will come with a “battery adder” as NextEra calls them in the USA. So at $3m/MW for wind and say $1.5 m/MW for solar that’s $1.5 bn per wind farm and over $300 m for a solar farm.

Now let’s look at the totals. Based on CIS Tender 1 the mix was about 45% solar, 55% wind. Notwithstanding brave claims that solar and batteries are competitive with wind I expect lots more wind to be built.

Overall the CIS calls for 23 GW of VRE (wind and solar) tenders and 9 GW of dispatchible power. The AEMO webpage says this is $52 bn of energy and $13bn of storage, or $68 bn in total.

Although the AFR and the Australian love nothing more than to talk about the cost of the new capacity I like to look at the QLD LNG industry for comparison. There the three projects spent around A$70 bn and probably had it been done by one able profit oriented owner (ie not a Govt) might have been done for at least $10 bn less maybe more. And final capex was between say 30% to 50% above the initial FID estimates. And that was 15 years ago. In today’s money the numbers would be higher.

I guess the point here is that the QLD projects were financed despite the cost over runs and with delays of 6 months to two years. And even more to the point despite having to build not one, not two but three pipelines from the Darling Downs.

As to whether the projects have earned the returns expected that is a complex question but I expect the answer is no. Its very clear that the Origin and Santos share prices performed terribly during construction supporting the old adage that for a resources project the best time to own it is when the discovery is being made and the second best time is after its fully commissioned. There is no third best time, only a worst time.

If we add in the transmission buildout the cost is comparable to the QLD LNG buildout. Or at least it would be if we didn’t include the Victorian offshore wind. The capital cost for that offshore wind build is likely to exceed $50 bn maybe even $60 bn, broadly comparable to the total that all the other States will spend together.

Financing and capital deployment

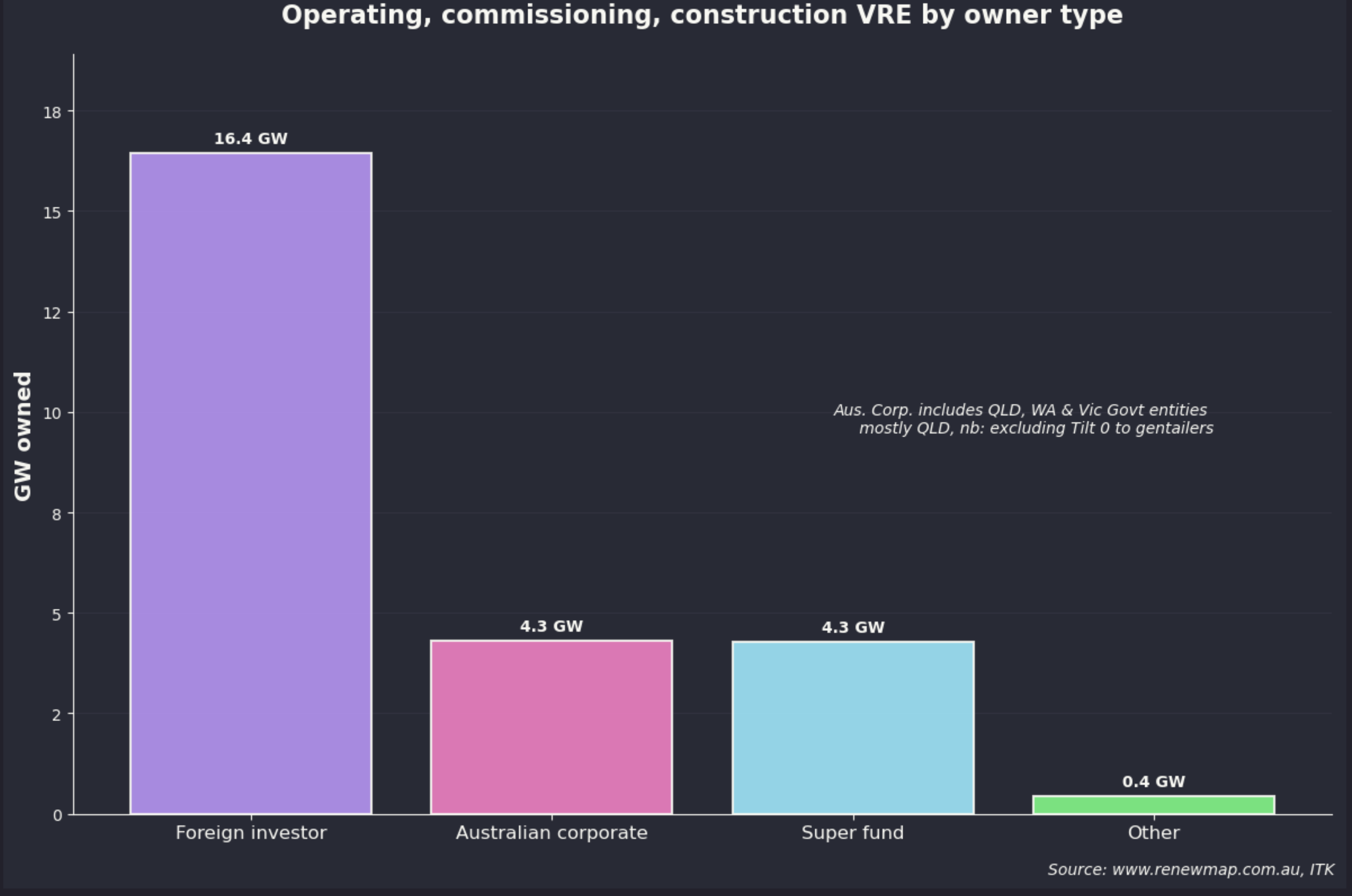

There are about 67 owners listed for VRE (wind and solar) projects that are in the OCC (Owned, Commissioning, Construction) deployed stages. However some of the 67 are just variations of the same Group. I went through the 67 owners and classified them for the following summary results. I wouldn’t swear the classification are accurate but the broad picture certainly is.

Notwithstanding how often I write about it, it remains truly astonishing that if we exclude the for sale 20% of Tilt that AGL (chair:Miles George ex head of Infigen, 10% shareholder green champion Mike Cannon Brooks), then the total MW of wind and solar owned collectively by AGL, ORG, Energy Australia, Alinta and Snowy is zero or close enough to it.

And yes the massive, arguably out of control, mega super funds do have some investments in the sector but they are not for the most part true believers. Super is discussed further below. So the vast bulk of ownership falls to offshore corporates, whether that be Brookfield or Acciona or Petronas, or Engie or a wide range of other foreign direct investors.

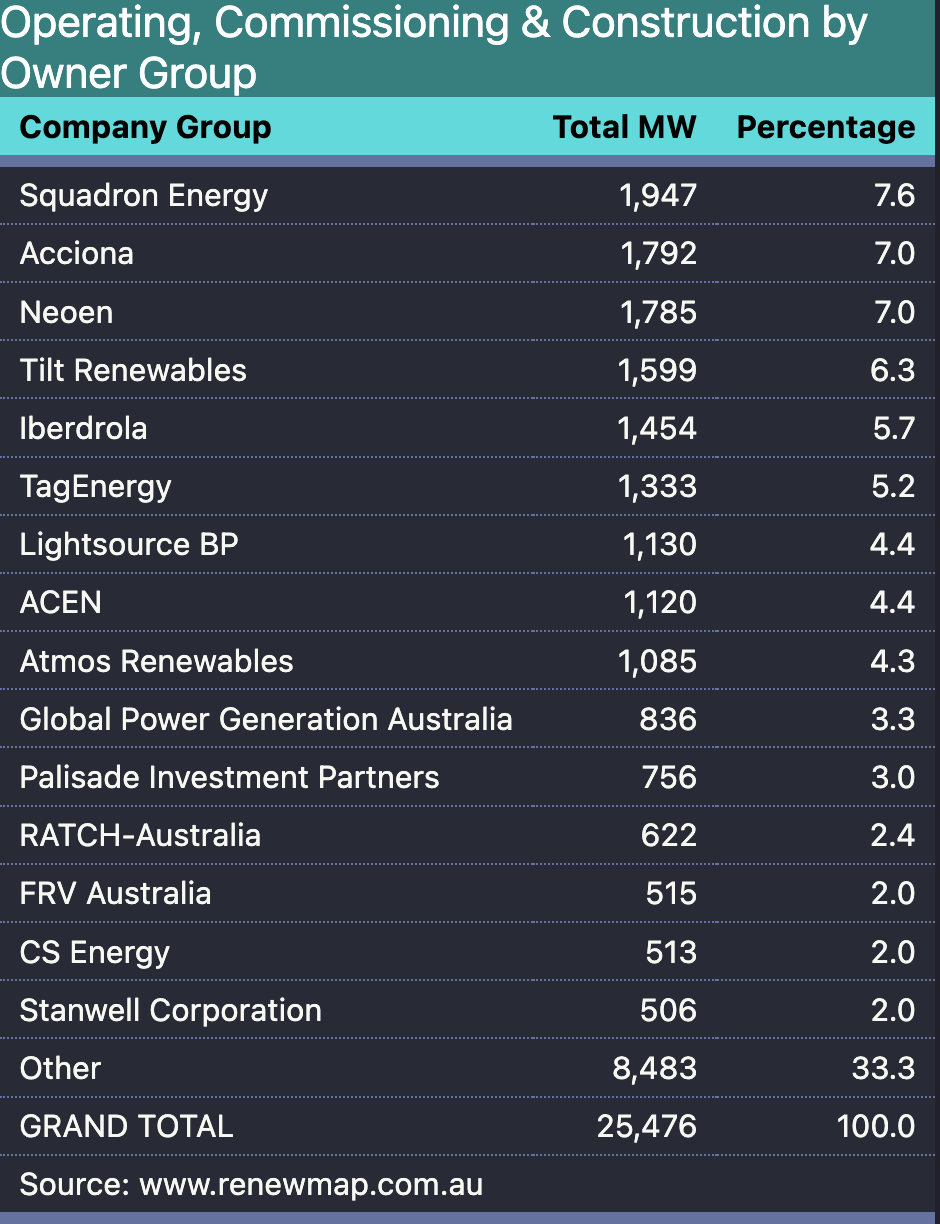

Looking at the names instead of the categories and grouping seemingly related groups together the ITK ownership summary for OCC VRE is as follows noting Neoen is Brookfield now. Still the table is instructive.

Squadron is an Australian company and Tilt is owned by the Future Fund and QIC. Palisade is an Australian infrastructure investor funded by Australian superfunds. CS and Stanwell are ironically QLD Govt owned. In fact the irony of reality is that if you put QIC (40% of Tilt), CS and Stanwell as QLD Govt owned its like the largest owner of wind and solar in Australia.

The brothers in arms won’t be doing the funding

The big three gentailers , ORG, AGL and Energy Australia, seem to have a joint and clear strategy.

Dominate the dispatchible market where it’s possible to influence pricing. ORG, AGL, and even EA along with Snowy dominate the dispatchible market. They do that by owning the coal, gas and hydro assets. I’ve already discussed this. To the greatest extent possible they would no doubt like to extend this into the battery market. At the moment though the battery market is in what I call the “cowboy” phase. Everyone has decided to be a battery developer, probably like when everyone in Iceland decided to move out of fishing and into investment banking. So while the cowboys are still building the brothers in arms will lose some share in dispatchibles. If history is a guide though after a while some cowboys will ride off into the sunset and the brothers will get a grip.

Although the gentailers clearly understand that their coal stations will close they want to extract maximum value from them while they are running and the best way to do this is to have passive resistance to new renewables. In practice this means not writing PPAs on new generation. To be sure there hasn’t been that much new generation to write PPAs against just recently.

The gentailers aren’t going to own any more wind and solar than they absolutely have to. The reason is that wind and solar have no pricing power. Even if you owned 100% of the wind or solar you still basically can only generate when it’s sunny and or windy. A monopoly owner of wind and solar could restrict output but it would be hard to manage. What they hope is that there will be a big supply of wind and solar needing PPAs in order to be financed, and this can be either pre construction or post construction, and then gentailers can be the off taker (the PPA writer) on their terms. To an extent this remains the case even with the CIS but the CIS hands some power back to the wind and solar developers as was pointed out by Anthony Fowler, CEO Tilt. Also in the end the gentailers will have to buy the output, the coal stations will close, the lights will have to stay on and the gentailers will need to supply their customers. In fact you could argue the longer they wait to write the PPAs the more the bargaining power will shift back to the wind and solar developers. Once built the capacity has negligible variable cost and will depress prices coal generators receive.

Still the conclusion is that the wind and solar has not and will not be owned by Gentailers, a new class of owner is required, and that is essentially an infrastructure capital provider. This contrasts with the CSG/LNG development in QLD where STO and ORG were happy to own equity in the projects. For the life of me I cant understand why, the risk adjusted return on capital isn’t that good and the share prices were killed during the construction. ORG took a A$1 bn write down on its APLNG investment in 2017 and a further small (maybe $100 m pretax net of fx reserve releases) impairment when it sold down a 10% stake in 2021. And APLNG is clearly the best of the QLD LNG projects, at least in my opinion. So I ask why see ownership of low carbon, good for the planet, wind and solar as bad for ORG shareholders and ownership of bad for the planet, loss making CSG/LNG as good for the planet? But we live in that world.

Australian Super funds aren’t rushing to do the financing either

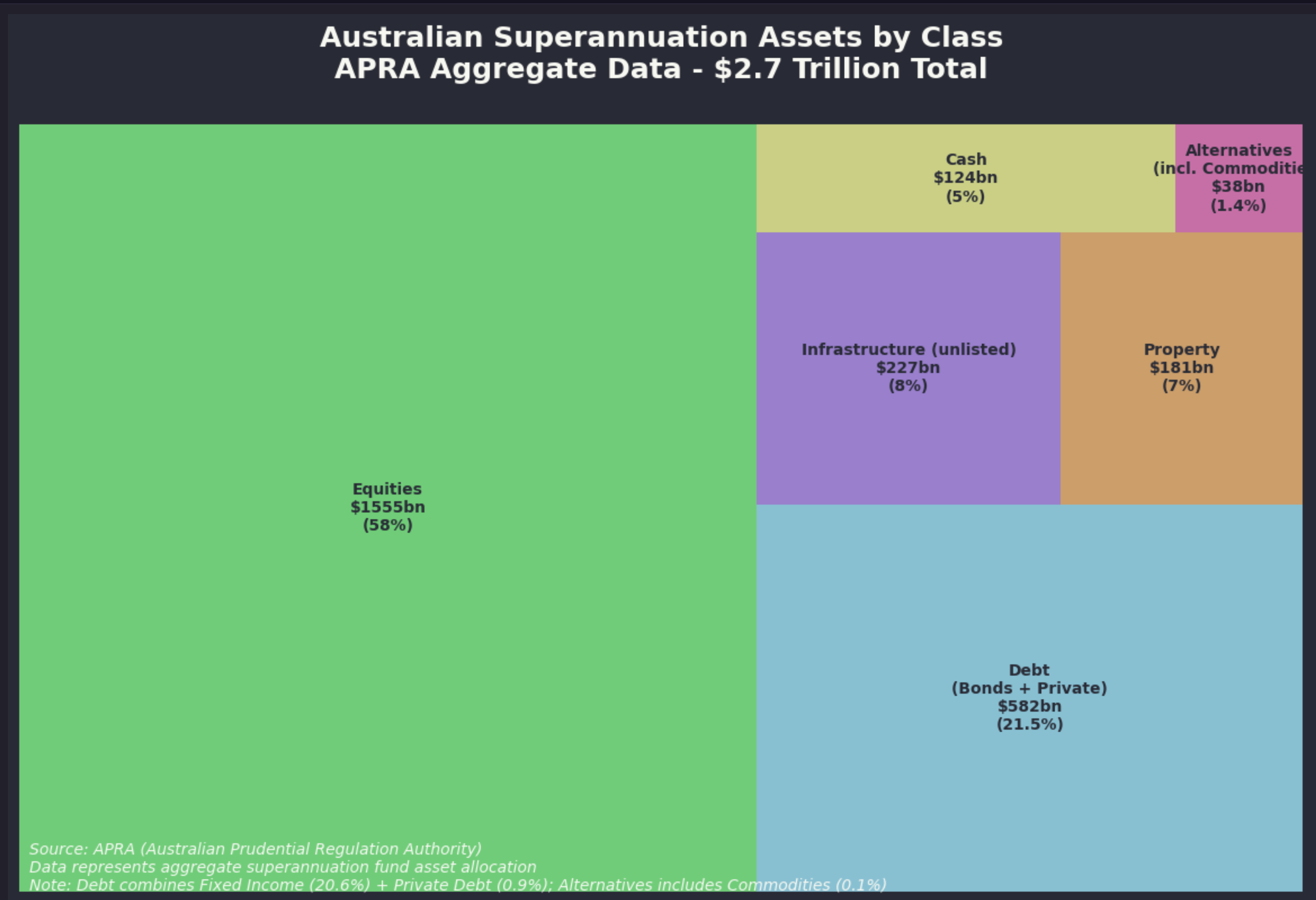

Australian super funds have become a law unto themselves over the past 20 years driven by compulsory saving. For the record ITK is completely in favour of compulsory super. However what I’m less enamoured of is the enormous market power that the large super funds implicitly have. The people running these very large super funds aren’t subject to the same processes that listed corporates are, that is the Boards don’t face relection or share price pressures. Nor are they subject to the same scrutiny as Governments where voters get to vote. Yet collectively they control just about $3 trillion of investments and growing every year. According to the APRA statistics about 20% of that or over $200 bn is invested in infrastructure. I would argue its very hard to get a good over view of what the actual unlisted infrastructure assets are or how they peform. However the point in this note is a bit more subtle. First of all here check the overall asset composition. These assets are both domestic and international but most of the international assets will be shares. The funds pretty much have to invest internationally because they have outgrown Australia.

So the market capitalisation of the ASX 200 is about the same size as the super sector. Within a year or two the superannuation sector will clearly be larger than the Australian stock exchange total market capitalisation. Of course that is comparing equity values with total assets but still.

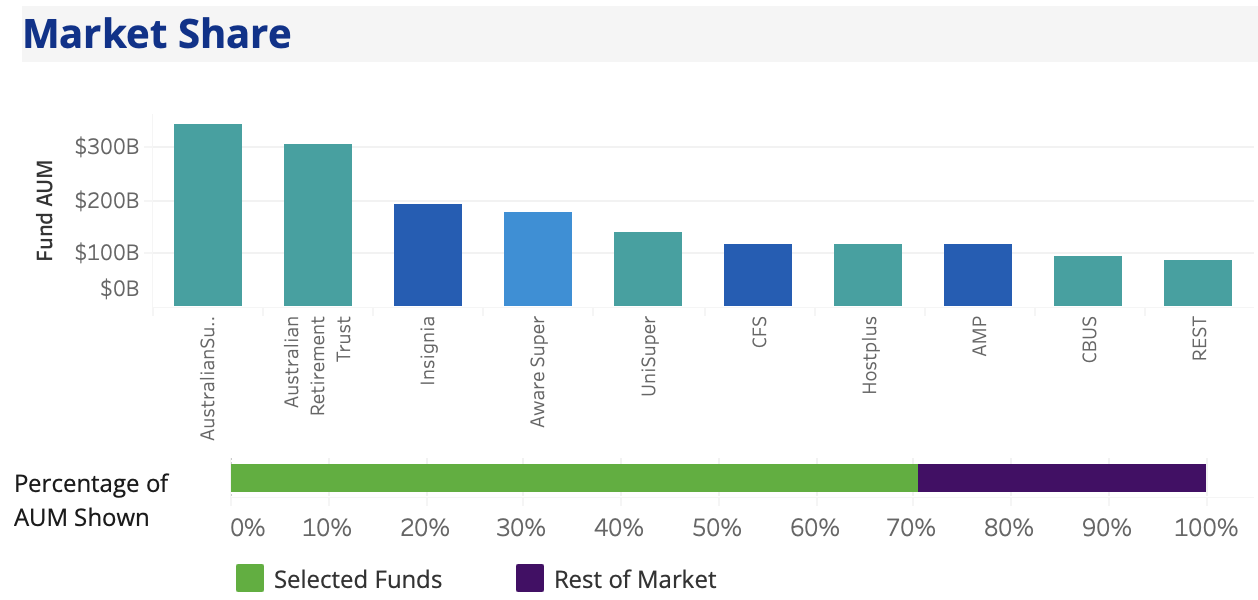

Within the superannuation sector the top ten funds have close to 70% of the total assets. Not only that, as a general statement they are the funds receiving the greatest net inflows. Although I could have created my own chart I’ve taken a screenshot of part of a KPMG visualisation which does a good job. Colours show type of fund, ie industry or retail. AUM is assets under management.

The so called mega funds have a greater allocation to infrastructure assets than the rest of the industry. But it remains hard to get a good feel. QIC is not a super fund but it is a major owner of infrastructure assets, and one of the major shareholders of Tilt.

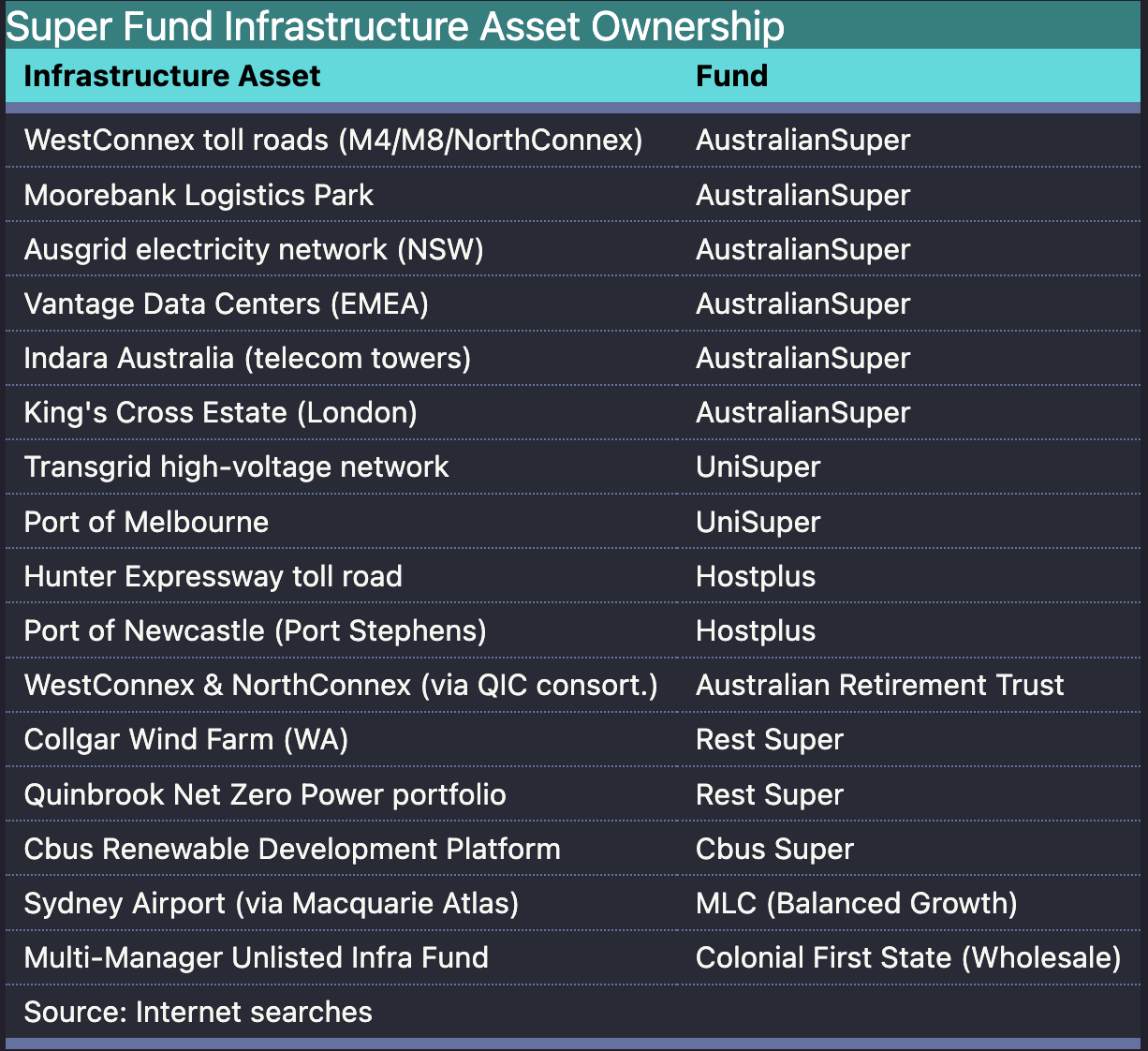

You can see from this list of infrastructure assets obtained by internet search of the various fund websites that the composition and makeup of infrastructure assets is relatively random.

Notes: (1) There is no easy way for an external observer to look at the performance of the unlisted infrastructure either as a class or at an individual level and (2) At least for this random set of searches renewable energy assets are not coming up a lot in the searches.

And that tends to confirm my prior perception that the big super funds don’t really give a rats about decarbonisation in general or decarbonisation of Australia and Australian electricity generation in particular.

Toll roads, ports, airports wonderful stuff, wind and solar assets more of a box ticker.

There is also a technical issue as regards unlisted infrastructure and that is the “my super” performance rules tend to make investing in low risk, low return, or green fields capex difficult.

MySuper returns issue - Transmission cant easily be owned, neither can wind or solar

MySuper returns is a complex issue but the bottom line is that valuing illiquid unlisted infrastructure is full of the potential for error. It simply becomes a valuers opinion. Unlisted infrastructure is presently measured, for MySuper purposes as a fund asset class performance relative to MSCI Australia Quarterly Infrastructure Fund Index. The MSCI Australia Quarterly Infrastructure Index represents a composite of core Australian unlisted infrastructure assets/funds. It captures returns from assets like transport, energy and utilities projects held by institutional investors, with periodic revaluation of assets rather than daily market pricing. According to Deloitte ” In the case of unlisted infrastructure, investments which differ vastly by sector, geography and stage (i.e. greenfield, established or anywhere in between) are compared with the same index.” Without going into too much more detail the incentive is to “index hug”. This means owning the same sorts of other infrastructure as other funds. It also means neither taking too much risk or too little. So everyone ends up the same assets, there is little innovation.

It also means, as Transgrid management will explain, that regulated assets are disadvantaged and its why the CEFC is required to step. The average return on a wires and poles monopoly regulated asset is less than the return on the average asset in the MSCI index. The return is lower because the risk is lower, and in fact regulated asset owners have done very well, but MySuper rules makes it hard for superfunds to invest in the electricity sector even if they wanted to.

I certainly don’t know what the answer to this is or indeed how serious a hinderance MySuper really is to Superfund participation in the Australian electricity industry but it does seem like something worth discussing.

Foreign investors get to own the industry by default

If the gentailers aren’t going to provide the equity and take on the debt, and the super funds aren’t going to do it either and the assets are still going to be in the private sector, and there are no listed companies that want to own the assets then by default what we are left with is what used to be known as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). This will be the Brookfields, Canadian Teachers, big international utilities like Acciona.

Is this really the way we want the industry to be structured? I don’t have a problem with it, there is no doubt that RWE or Acciona are at least as powerful in an PPA negotiation as AGL or ORG but a lot of capital is going to be asked of them over a short space of time and there will be some long meetings in European, North American and Asian capitals about whether the risk and return in a foreign country is justified.

My personal feeling is it would be nice if Australian super funds took Australia’s decarbonisation more seriously and instead of buying Nvidia or Alphabet or Facebook instead worked out to individually and as a group put say $30 bn into the wind and solar sector.

The superfunds dont have to directly take responsibility for the construction risk, that can, at least on paper, fall to the developer. Arguably if you are going to own the kit you need an operator, so there would have to be a vehicle that provided operations. In theory spreading operations expertise over a big portfolio might lower costs.

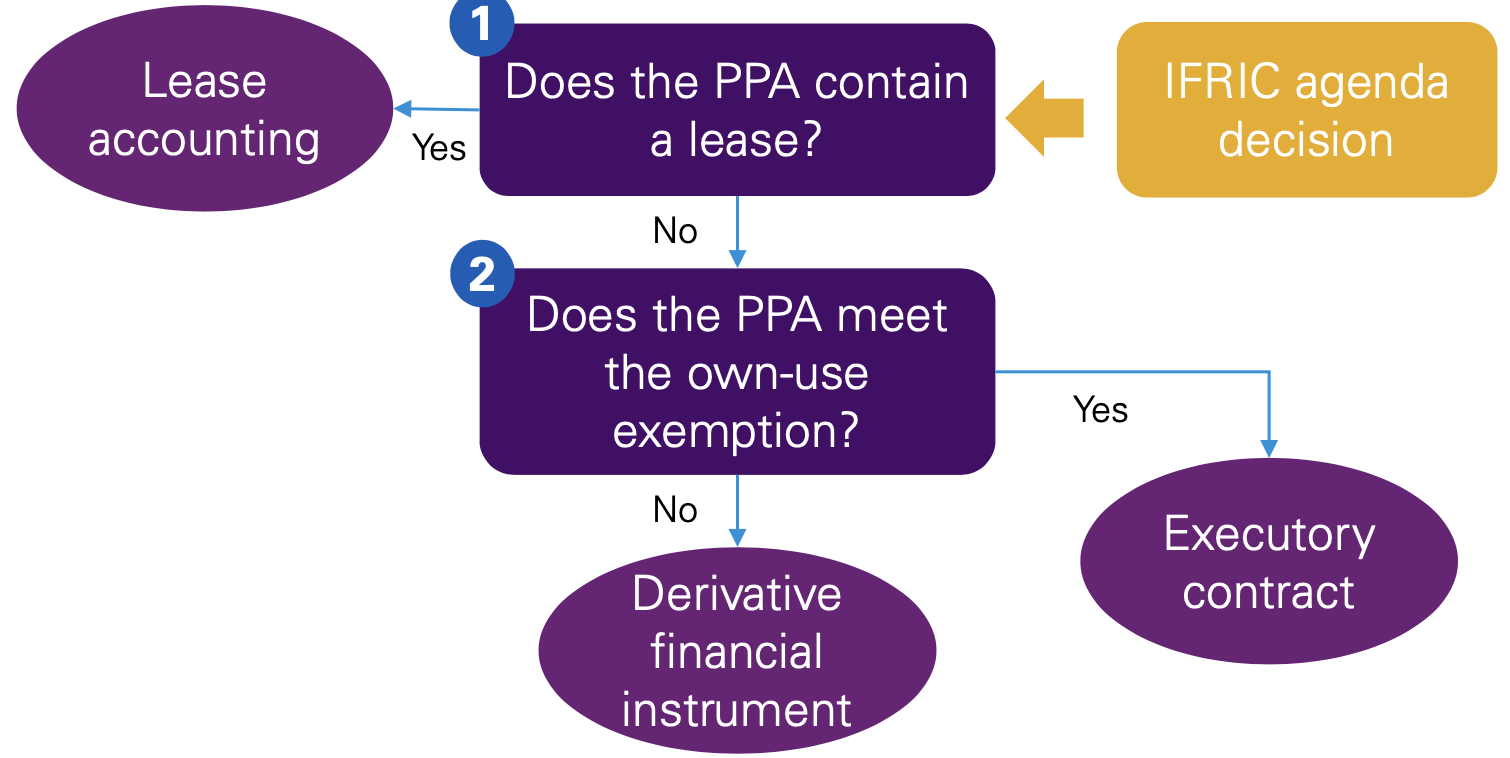

PPAs are executory contracts for the most part

In practice in my personal opinion if it walks like a lease and quacks like a lease then it’s a lease. However because a PPA (purchase power agreement) doesn’t generally transfer control of an asset (batteries might be different as the buyer of the battery output can control dispatch) then a wind or solar PPA is not a lease.

KPMG published a good note on the topic in 2022

In fact going forward, and following some international amendments which will be operative from 2026 onwards most PPAs are likely to be accounted for as executory contracts.

The amendments allow a company to apply the own-use exemption to PPAs if the company has been, and expects to be, a net-purchaser of electricity for the contract period. (Source:KPMG 2024)

Most gentailers and other buyers of electricity will be able to satisfy the own-use exemption I’d have thought, and therefore the PPA will not need to be treated as a derivative.

However as I read it if the PPA is accounted for under the own-use exemption details have to be disclosed, to wit:

- contractual features exposing the company to variability in electricity volume and risk of oversupply;

- estimated future cash flows from unrecognised contractual commitments to buy electricity in appropriate time bands;

- qualitative information about how the company assessed whether a contract might become onerous; and

- qualitative and quantitative information about the costs and proceeds associated with purchases and sales of electricity, based on the information used for the ‘net-purchaser’ assessment.

Other than the disclosure obligations noted above the purchase obligations under a PPA are not recognised as a liability unless they are sufficiently “out of the money” to be treated as an onerous contract.