Australia is not alone in decarbonising and our coal industry is falling behind

It seems to me that Australians are quite parochial when it comes to covering decarbonisation. It’s all about what political leaders say. There seems little interest in where Australia sits in the global context.

So it’s quite common to hear that Australia is out of step with the rest of the world with our 2035 commitment, that we are recklessly embracing renewable energy and we are doing what no-one else has and therefore it’s doomed to fail and make our electricity industry uncompetitive and our heavy industry uncompetitive. Soon we will have to rewild the country and build new coal and nuclear stations so that we can once again have globally cheap electricity.

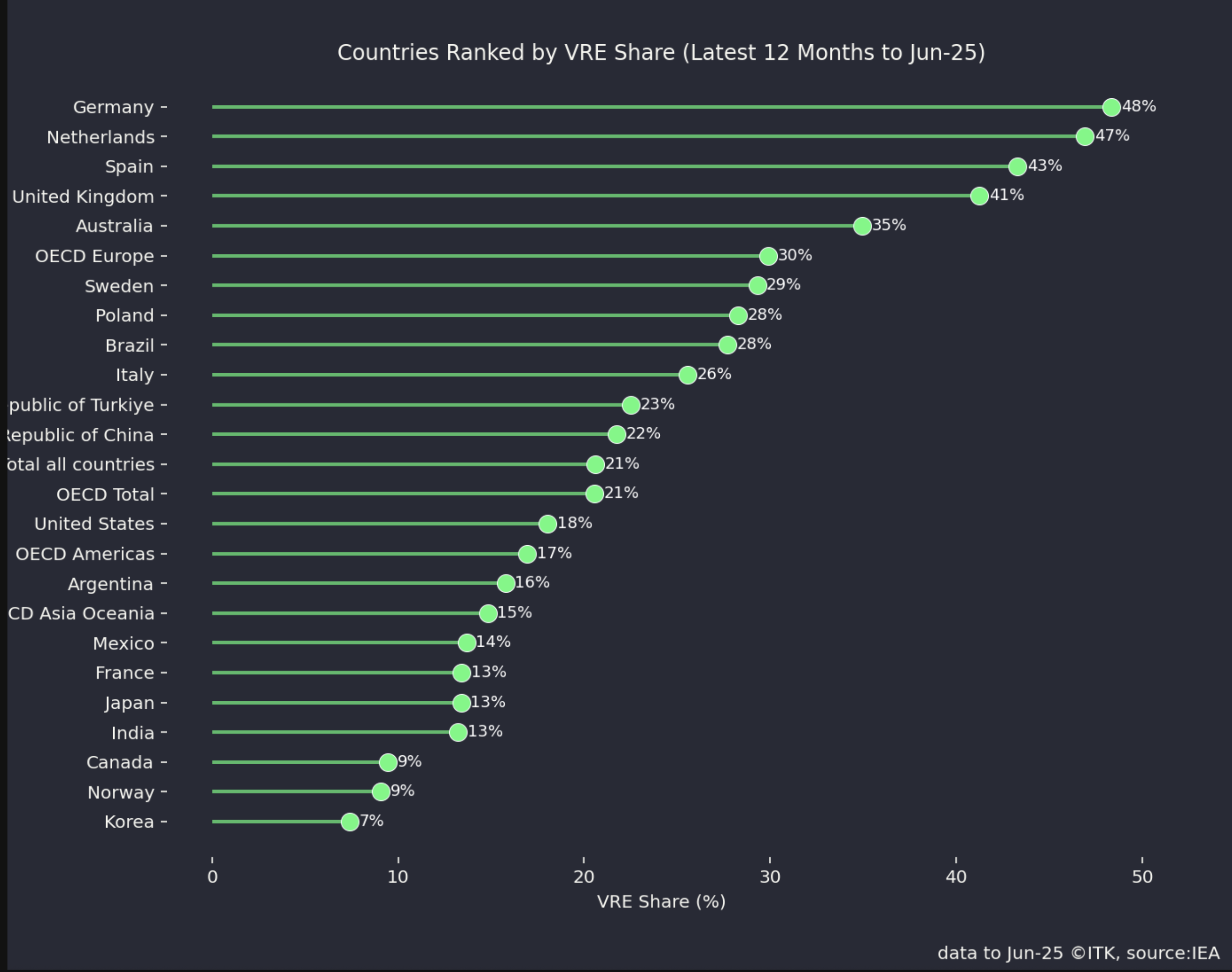

In this note I started by taking IEA statistics that shows that we are in the top 1/3 of countries in our share of VRE (wind and solar) but that most countries are moving in the same direction at a greater or lesser speed. In terms of renewable share we would be much lower on the list if I had included hydro and nuclear. Then the South American and European countries would move further up the list. But I focus on wind and solar because that is what is growing everywhere all over the world and therefore we are all going to see what that means for electricity prices and firming and frequency control.

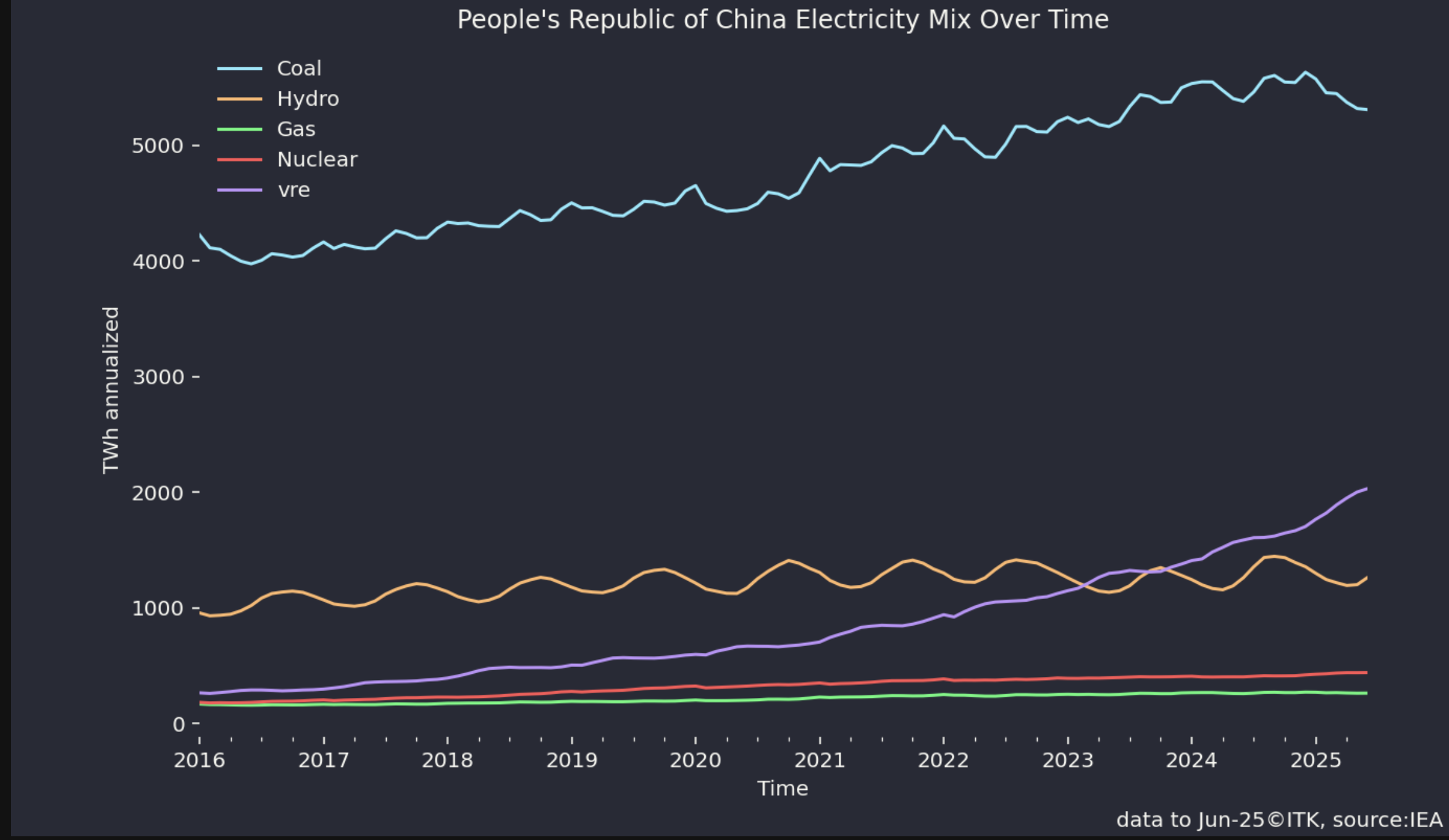

In particular as a long time if a no account and distant China watcher it’s interesting to note that China now gets 22% of its electricity from wind and solar, only a few years behind where Australia was, and as usual moving much faster.

In this note I don’t then go on to look at EVs. If I did Australia would likely still be at best in the middle of the pack but probably in the bottom 50% certainly way behind China and Europe. In my opinion because price elasticity of demand for oil is high, the lower growth in demand is already showing up in the oil price but how that plays out will be clearer in a few more years. But in any case Australia is a fairly distant follower not a leader.

So the world, in my opinion, is decarbonising not fast enough from a carbon perspective, but fast enough to impact economics, that is demand for industrial minerals like copper, but also impacting oil and coal demand at the margin.

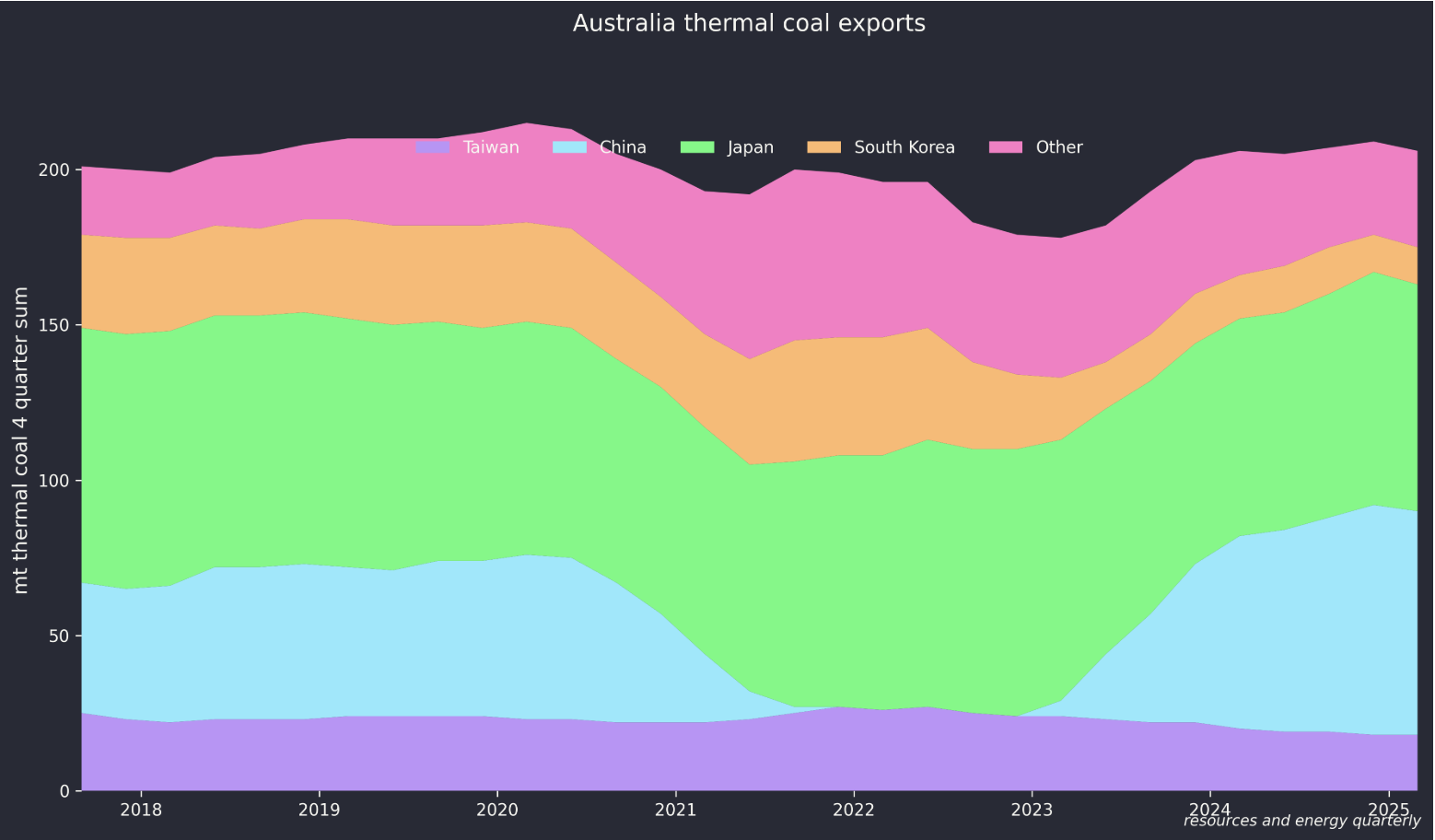

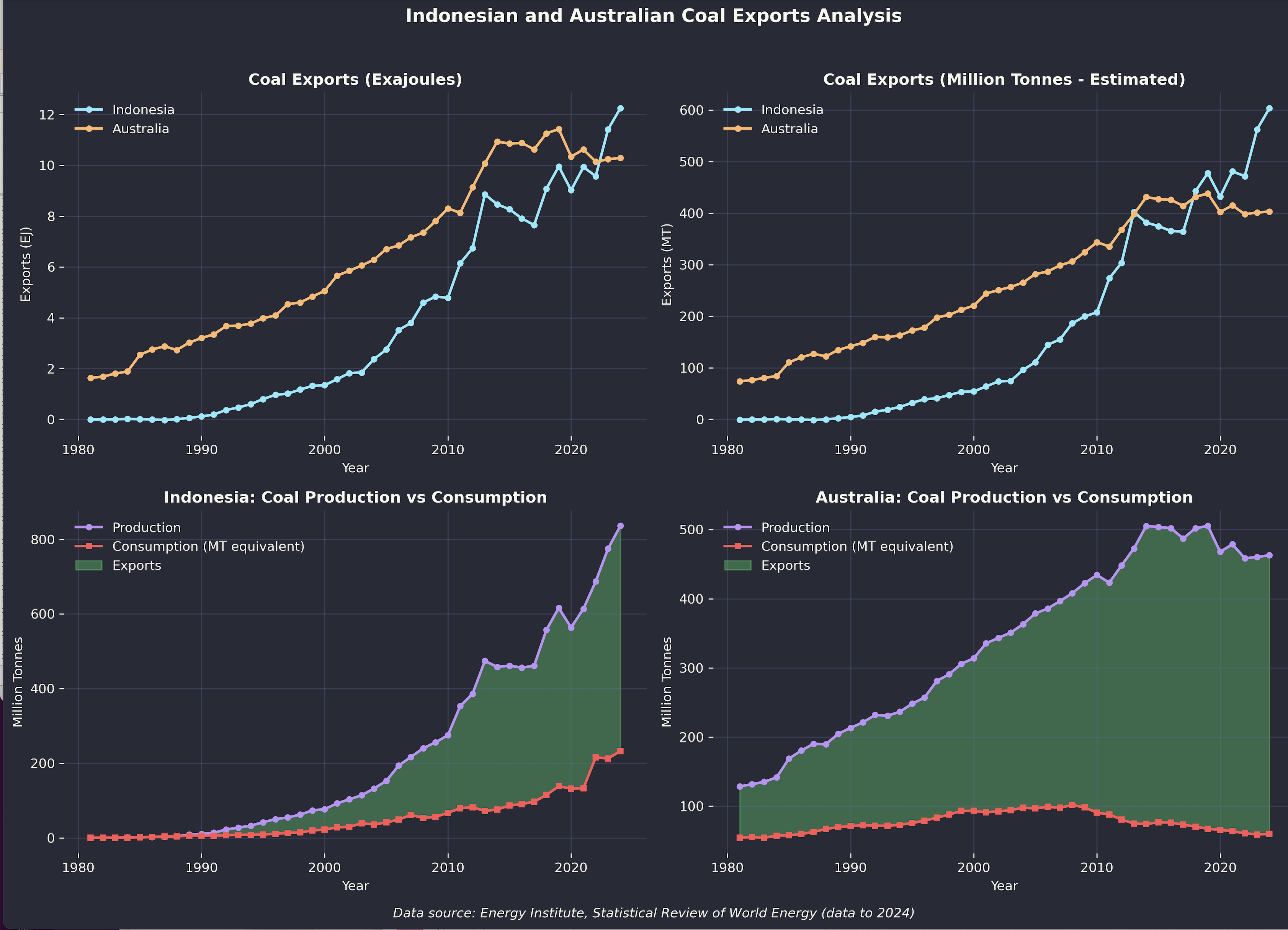

Since Australia is a major thermal energy exporter, on my estimates the second or third largest, and since oil imports impact our balance of trade and are a security risk it’s therefore interesting and important to look at coal exports and their prospects. And this is where the surprise, to me, in this note comes from.

Specifically Australia’s coal exports are flat. Thermal coal exports have been flat for about 8 years. But I don’t really think the major direct cause is less demand for coal. What the numbers seem to show is that Australian coal is uncompetitive with Indonesian and Chinese coal. So China has expanded its domestic production about 1.2 bt over the past 10 years, undoubtedly by far the biggest contributor to higher global carbon emissions. Indonesia’s coal exports, particularly low quality but super cheap, have also grown by several hundred million tonnes. Indonesia has taken market share from Australian thermal coal. As to why Australian coal has become less competitive is for others to decide. Certainly, and I am in the fan club, there is an anti coal movement in Australia that makes new mines expensive to develop. We need such movements in Indonesia and China. So its economics that are killing Australian coal exports just as its domestic gas prices that have killed domestic gas consumption. Global decarbonisation is playing a role but it’s a dampner ,not yet from Australia’s perspective, the lead. But if Australian coal is going to struggle all the more reason to find the next gig. All the more reason to decarbonise and embrace the future.

The other tentative finding from this note is that China’s coal mining, coal generation and to an extent steel making industries are all interlinked. At the moment China can tolerate the growing share of wind and solar, now 22% of production, because overall electricity demand has been growing which means that coal generation is broadly flat. But should electricity consumption growth stop then there will be the usual economic fight between wind, solar and coal generators. Since there are millions and millions employed in the coal mining and coal generation industries wind and solar owners will struggle to win that fight.

Global decarbonisation of electricity

One of the risks to Australia decarbonisation target is that we might be doing it on our own. I’m fond of military analogies, so my analogy here is that just because we are one soldier among many what we do counts as much as what any other soldier does, but equally there is no point being the soldier that charges the enemy line all on their own.

When you look at the data we are not doing it on our own. Whatever you might think of IEA forecasts they have some great statistics. The following plot shows the VRE (combined wind and solar) share of total electricity consumption for a particular country or region for the 12 months ended June 2025. I filtered the database to get the top half of the electricity consumers, which meant leaving out some small countries with big renewable shares. And I’m only looking at wind and solar here; if I included hydro and, yes, nuclear, Australia would be further down the list.

The global total, that is all the countries in the IEA database, which does exclude Russia, is about 21% VRE.

Among the major economies, China is at 22% wind and solar. The following plot shows how China has grown its VRE share and there is now a hint but only a hint that coal generation is starting to fall off.

And actually I’m doubtful that the China data includes behind-the-meter. Even India and Japan, basically global laggards have pushed their VRE share up to 13%.

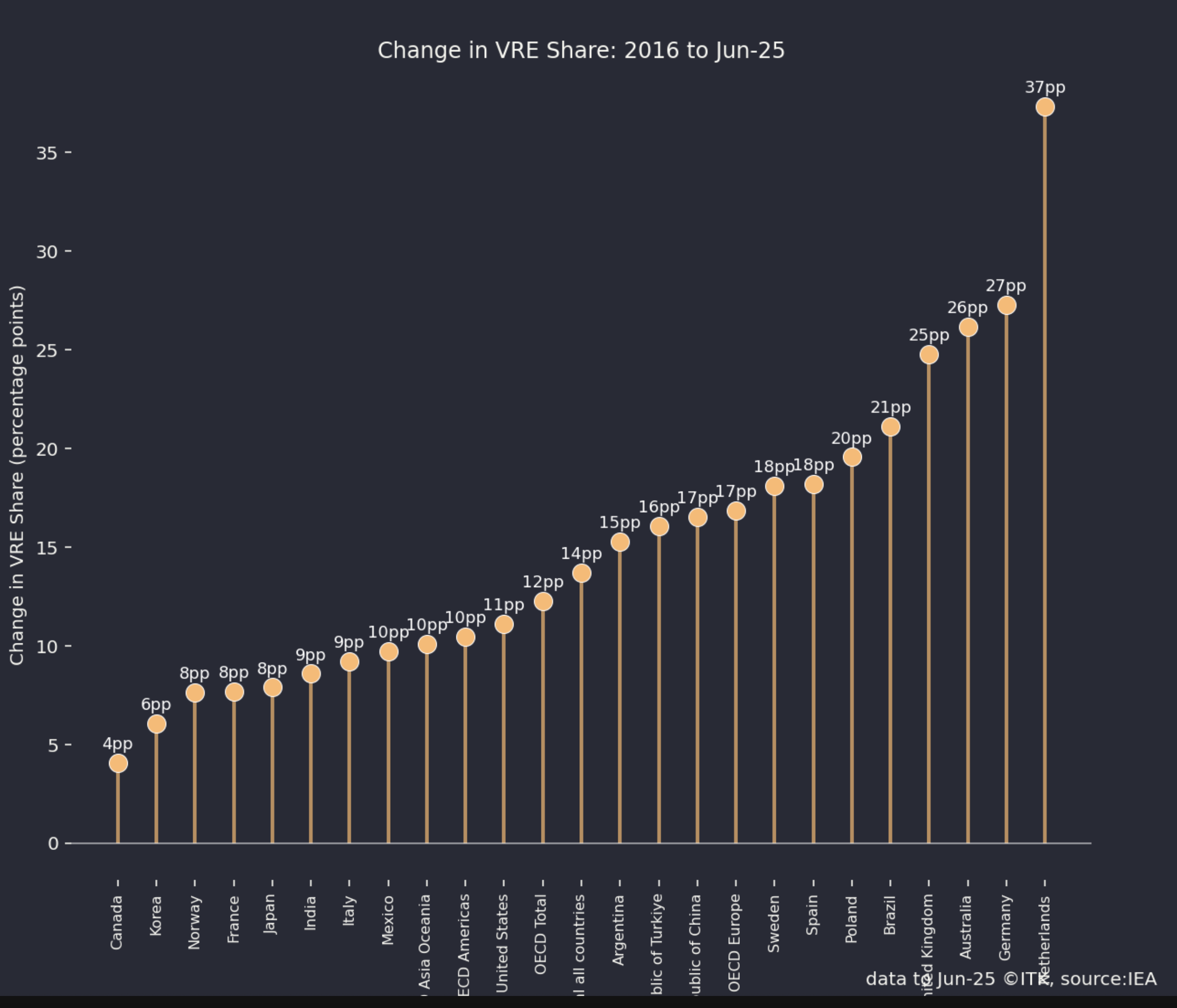

And then if we look at the pace of change Australia is close to the top but I suspect China will be higher this time next year.

If you look at the global total (total all countries) it’s increased 14 percentage points in nine years, from 7% to 21%. Of course that isn’t fast enough and the share is still far too low, but the gears are turning and the mill will grind.

So for me the trends are clear and it IS entirely appropriate for the Australian Government and Australian business to get ahead of the curve and start to position ourselves for the new world. Consider next our thermal coal exports.

Not yet falling but thermal coal exports are ex growth

Australia’s thermal coal exports have been essentially flat for the past 8 years. The chart below goes only to March 2025 and more recent data would show China imports from all sources falling.

You can see the drop in exports to China when there were political issues, but you can also see, or at least I can, that Japan and other countries simply bought the coal and then most likely on sold it either directly or through other intermediaries to China so that the ban was largely ineffective from a volume point of view.

But the real point is the lack of growth. Part of this may just be cost and price competition. Indonesia has gone from strength to strength in thermal coal and probably South Korea buys more from them and less from us these days. This can be seen in the following plots noting that exports have been calculated as production - consumption and possibly overstate Indonesian exports by as much as 50 mt in 2024. Still I think the general trend is clear: for one reason and another Indonesia’s generally lower quality coal has taken market share from Australia and Indonesia continues to grow coal production and exports whereas we are basically flat in Australia. It’s also interesting to note the sharpish growth in domestic Indonesian consumption.

One might argue that Indonesia deserves more attention from the climate universe than it currently receives.

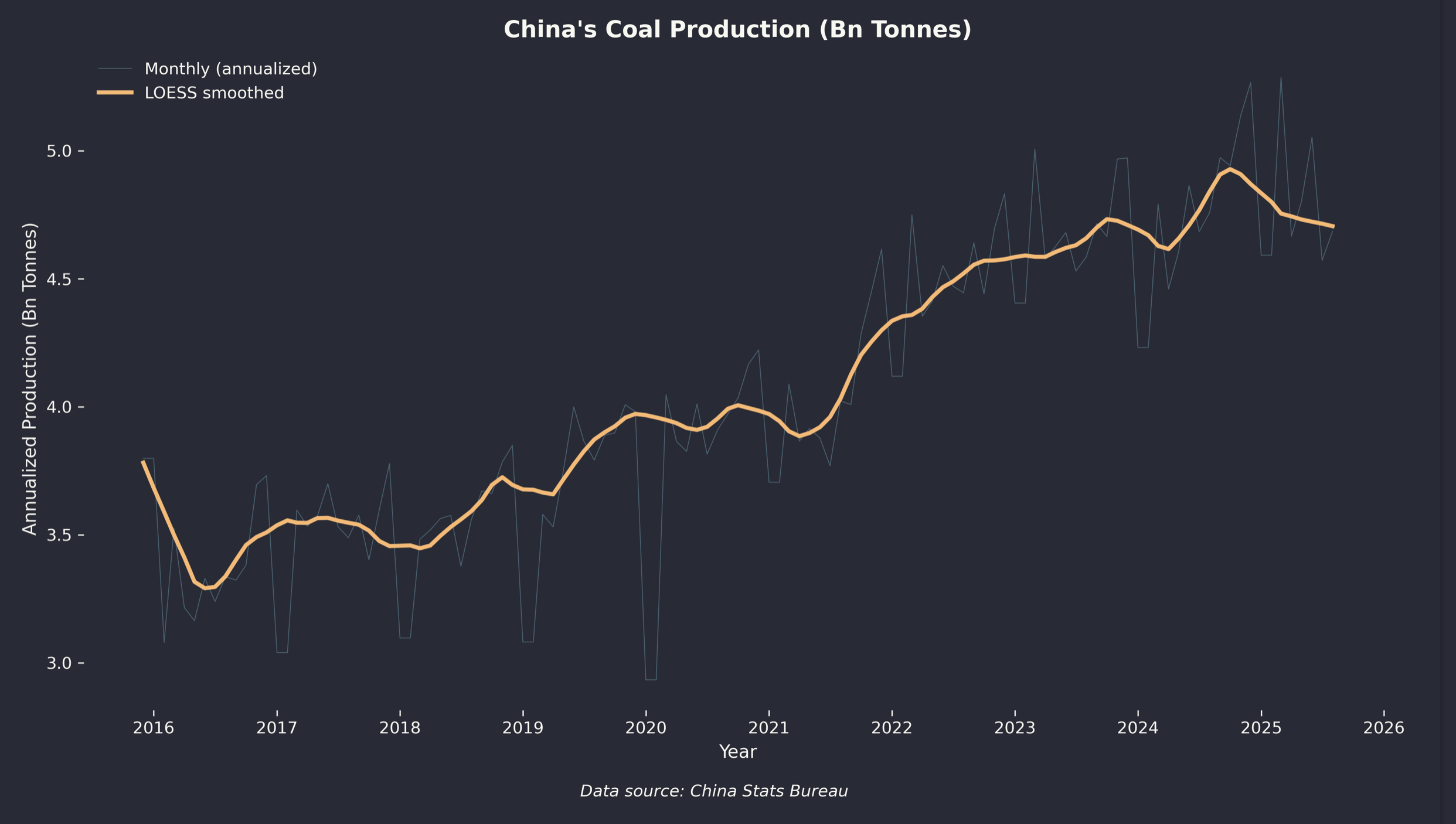

Indonesia’s production growth is dwarfed by China where production has grown from 3.5 bn tonnes to about 4.7 bn tonnes in nine years.

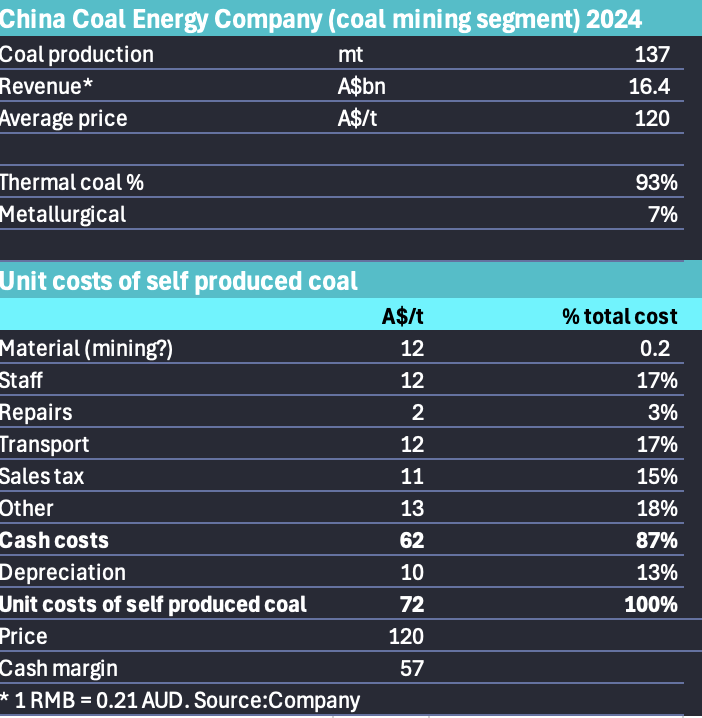

If you are an optimist (are there any left?), you might say production has peaked, but we’ve been here before. The thought was coal production had peaked in 2016 but it’s now more than 30% higher than that level. It’s also likely that there are some excellent operators in China’s coal industry. I looked at management commentary for one new China coal mine which was at a capital cost of A$0.9 bn for 2.5 MTPA which works out to less than A$20/t of depreciation.

It’s likely that China has a huge number of coal mining companies, some big and efficient, most probably not so much. I took these numbers from China Coal Energy Company which produces 137 mt of coal, equal to about half of total NSW production and that’s just one segment of its business. Anyhow the point of the table is it looks quite profitable, so coal prices would have to fall quite a bit for the company to cut back production.

Equally there are 2.5 million people employed in the coal mining industry, or so the studies I read indicate, and probably a lot more if the entire value chain was included and through to China’s coal powered electricity.

China’s coal quality (GJ/tonne) can be quite low, although not as bad as Indonesia but consensus estimates are probably around 20 GJ/t. That implies that about 2.5 bt of coal is used for power generation but when you do the sums and even allowing for carbon bombs like coal to gas plants of which China has a few, you will still find it difficult to see where the other 2 bt goes. It remains the case that most of the metallurgical coal required for China’s enormous steel industry comes from imports and much of that from Australia.