Overview

Green iron as a replacement for coal and gas exports

“We thought we could sit forever in fun, but our chances really was a million to one” - Bob Dylan’s dream

In brief - getting two birds with one pellet

Using an Electric Smelter Furnace may allow enough value adding to Pilbara iron ore by converting it to pig iron to eventually fully replace our coal and gas exports generating over $100 bn of export revenue at recent prices. So converting iron ore to green iron solves two problems at once. Firstly it significantly decarbonises steel which in total releases about 8%-9% of annual global carbon emissions. Secondly it provides the export income that Australia will require to replace coal and gas exports as those decline to zero over the next 25 years.

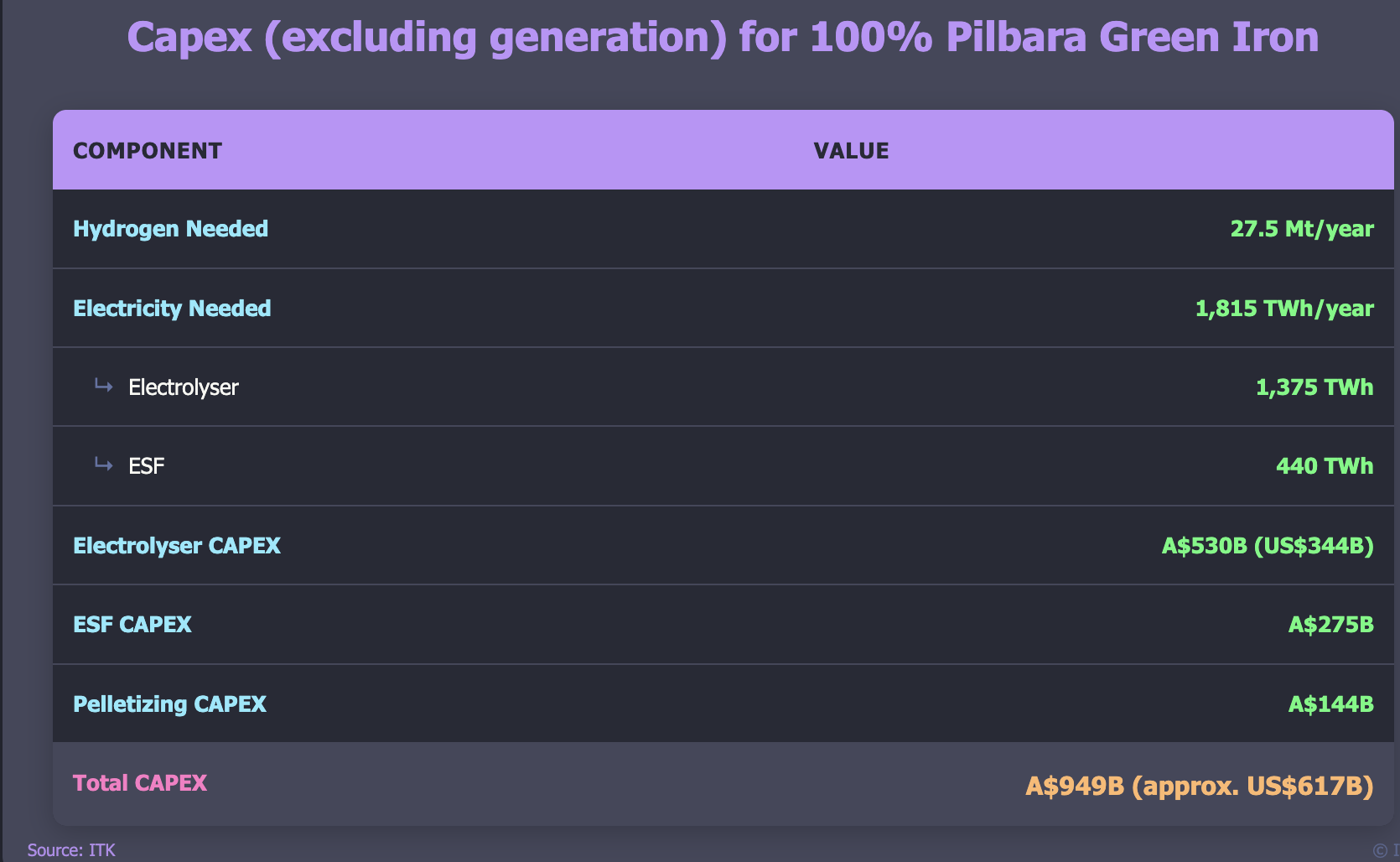

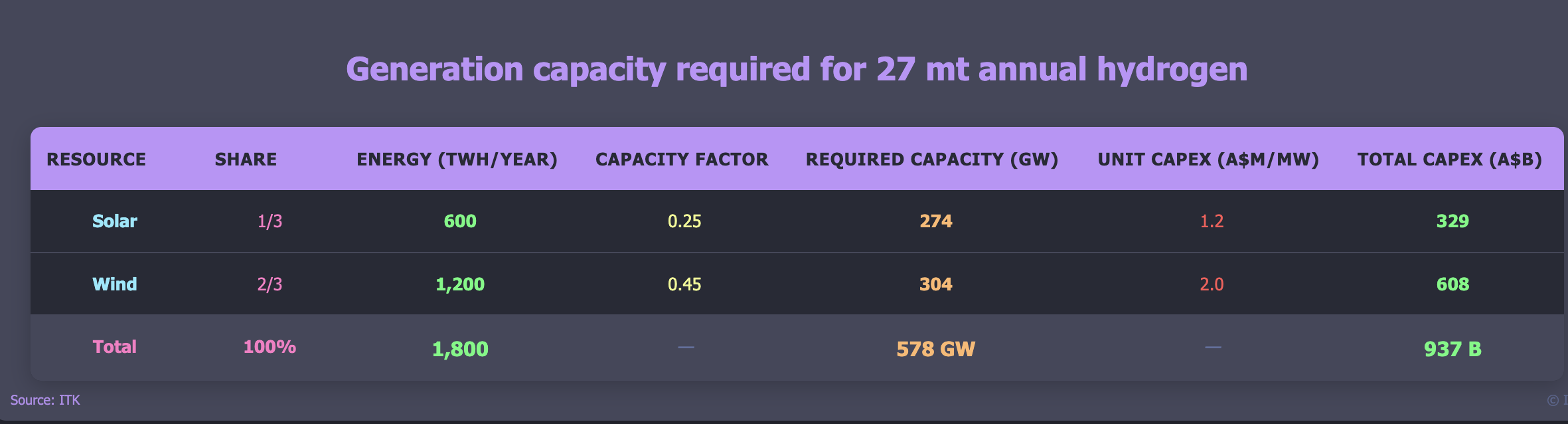

The opportunity is great but its largely unproven and the investment required dwarfs anything ever contemplated previously in Australia. 25 mtpa of hydrogen would be required consuming 1.8 PWh per year with about $1 trillion of electricity generation investment and another $1 trillion in electrolysers. It is possible that with enough scale the electrolysers could fall sharply in price.

Where are we on this journey? At the very beginning. The progresss that has been made in the past three years, or so it seems to me, is to identify a technology that can produce green iron at a reasonable cost from Pilbara iron ore. Therefore the possibility exists of success. The very fact that a pathway exists for Pilbara iron ore will incentivise RIO and BHP to check it out and perhaps become owners of the need and the opportunity instead of having to be pushed.

The major iron ore producers are contemplating building a 30kt ESF supported by $75 m from the WA Govt. That’s 30kt compared to Australian iron ore exports of 960 mt. Another early sign of progress is the Stegra Euro 6 bn green steel plant due to be operational in Sweden in 2026. It’s the first example of industry doing it for real instead of just talking or experimenting. Stegra is one to keep a close eye on.

Background

For a number of years I’ve been asking myself what could replace Australian coal and gas exports. To be sure I’m not the only person who sees that decarbonisation means that our second and largest exports will be no more in the fullness of time. Fortunately or unfortunately it will take time, more time than our descendants can afford but far less time than the coal and gas industry believes.

I recall in 2006 when I joined UBS the first thing my boss and friend asked me was how seriously to take climate change and that was because UBS in the UK had issued a big global report “the time for talking is over” and the report author was marketing in Sydney. I asked at the time what could replace coal for generation, because as recently as 20 years ago it didn’t look like there was an answer at least not until you did dive into the weeds, which I proceeded to do more and more.

Now of course we in the industry know with pretty much 100% certainty that although some gas is needed for the last 10% of the job (until hydrogen comes along) the electricity system can easily do without coal. Not just here but in Europe, in Texas, in California and increasingly even in China that is becoming more obvious all the time.

And so I hope it will be for steel. Even three years ago decarbonising steel seemed to me to be in the too hard basket with far easier to attain targets the first to be attacked, that is electricity and passenger cars.

But as I say that left the export issue. A part of it was replacing oil imports, that is negative exports, with electric cars. A part of it was around services, but to my mind hydrogen exports were unlikely to replace coal and gas because even though it costs more to make hydrogen in say Japan than Australia most if not all countries had the potential to make hydrogen if they wanted to but not every country had oil and gas.

So the market size had to be large. And of course a large market justifies investment.

Also steel is broadly responsible globally for between 7%-9% of global carbon emissions, So clearly steel is going to get attention no matter how hard the task is. That looked difficult for Australia because our iron ore didn’t for the most part, seem well suited to traditional methods of making green steel. Electric arc furnaces and direct reduced iron (DRI) run better on ores with less impurity in them, so called magnetite. Pilbara iron ore, although great for traditional blast furnaces and blast oxygen furnaces didn’t seem suited to green steel.

Academics and industry people in Govt would talk about green steel and the manufacturing opportunity and I would scoff.

Then I went to a Smart Energy session only a month or two ago and heard about an electric smelter furnace (ESF) Although I knew nothing about steel this was interesting because of the potential to work with Pilbara iron ore and because I have been looking as a financial analyst at aluminium smelting for a long time.

Then I found out that a consortium of Rio,BHP,Bluescope and regretablly WPL are actually seriously contemplating building a small but not that small (30kt) ESF. And then I looked at Europe and found that the Europeans are spending via Stegra about 6 bn euros on an integrated green steel plant. Ie doing it for real.

No decarbonisation without exports

Australia is the world’s second or largest exporter of fossil fuels. The burning of those fuels is responsible for about 2% of annual global emissions. The transport of them is also a significant carbon emitter. In the end reducing our own carbon emissions won’t be enough. Either we will have to initiate or other countries will force us to stop exporting fossil fuel energy.

The good news is that we probably have ten years more to develop a viable export industry to replace fossil fuels.

At the moment there are three pathways:

- Hydrogen export. Although it looks the easiest my own view is that hydrogen’s problem is not so much its cost but rather that in the end most countries in the world will be able to produce green hydrogen and even if the production cost in other countries is higher, the large hydrogen transport costs will mean Australian hydrogen will struggle to be competitive with offshore domestic produced hydrogen. There may still be opportunities for hydrogen exports to Asia and for that reason development of the domestic industry should continue to be supported. But its no sure fire answer.

- Export of electricity via underground DC cable eg Suncable. This may still be viable but it’s not going to be the entire answer unless there are also cables from Singapore to countries further afield. At the moment this still looks far too risky and niche to see it as a major part of the answer.

- Domestic manufacturing using renewable energy. Within that category iron and steel have emerged as major contenders despite the enormous difficulties. The reason for iron and steel is that the industries are big enough and we already export 38% of the world’s ship born iron ore. And of course iron ore is our number 1 export. So the focus.

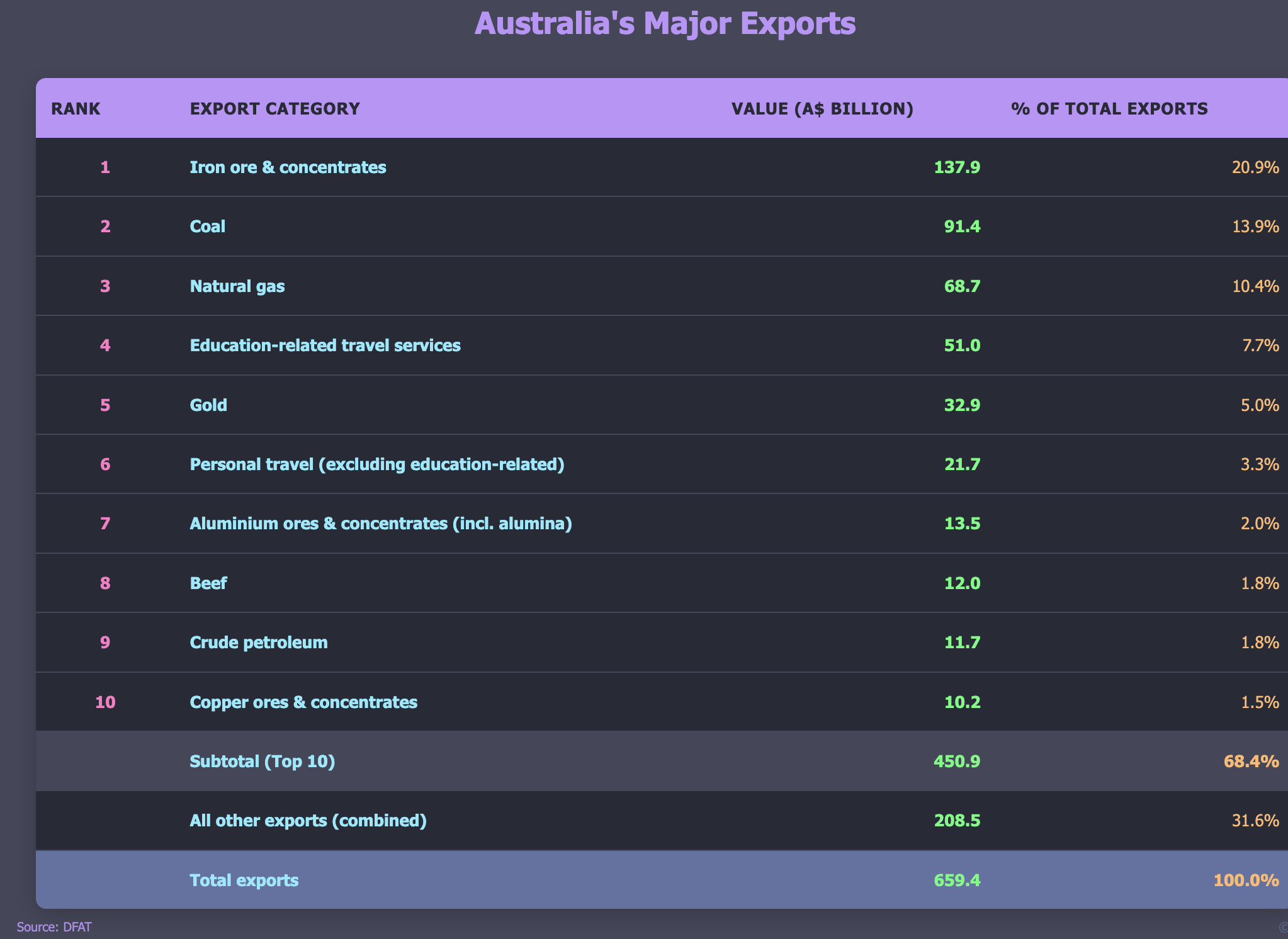

Iron ore exports are as large as coal and gas combined.

Value adding via green iron.

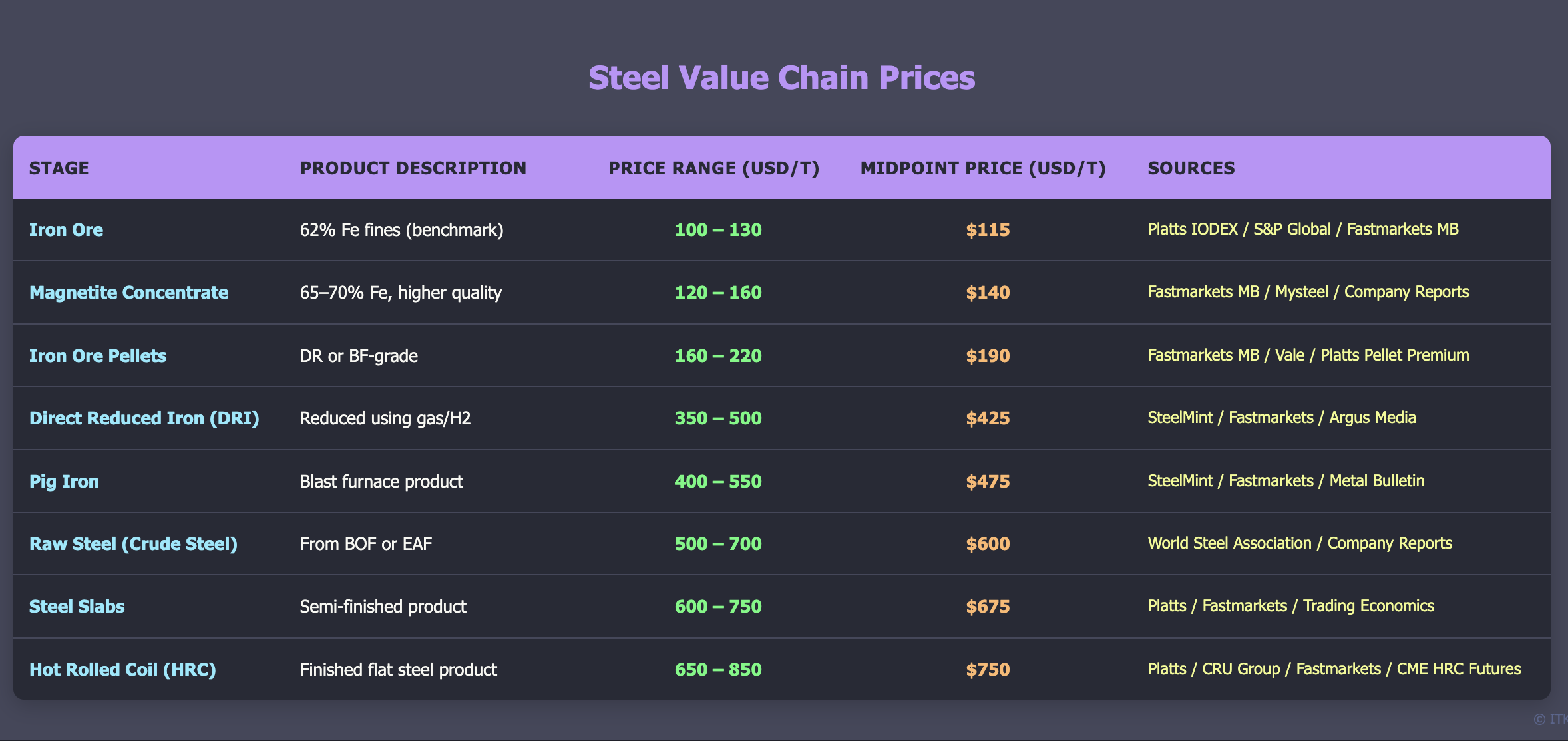

Iron ore pricing reflects global benchmark seaborne fines on FOB Australia basis. Magnetite concentrate pricing incorporates DR-grade or high Fe concentrate premiums often inferred from company reports. Pellet pricing includes base iron ore cost plus pellet premiums ranging $50-70 per tonne. DRI prices reflect traded markets primarily in MENA, India, and occasional export transactions. Raw steel pricing derives from cost structures and furnace economics rather than direct trading. Steel slabs reflect export prices from major producing regions including Brazil, Russia, and Southeast Asia. Hot rolled coil represents the most liquid traded flat steel product with established benchmarks across US, EU, China, and Southeast Asian markets.

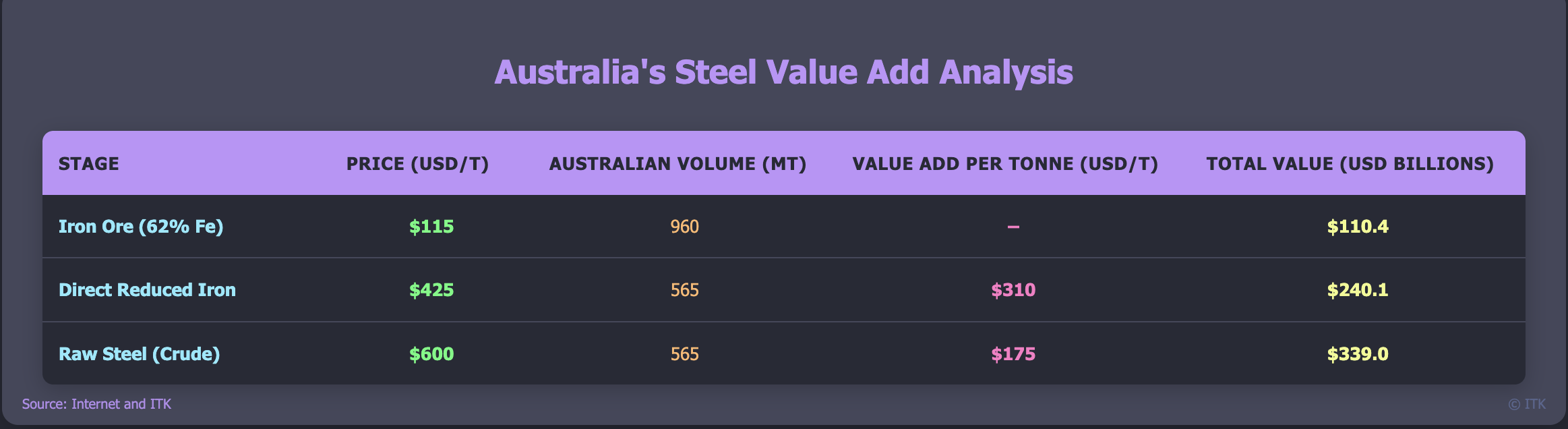

Using the table below of products in the steel value chain there is an opportunity, before costs ha ha of adding as much as US$130 bn of value by moving from iron ore to green iron.The transformation of Australia’s 960 million tonnes of iron ore production through value-added processing demonstrates substantial economic opportunity. Converting iron ore to DRI creates $310 per tonne of value addition, while further processing DRI to raw steel adds an additional$175 per tonne. The total potential value creation reaches $339 billion for raw steel production compared to $110.4 billion for iron ore exports, representing a threefold increase in export value through domestic processing and beneficiation. Of course at the moment that is completely uneconomic.

Decarbonisation of steel is a potential high risk, very high cost potential opportunity to replace thermal energy exports

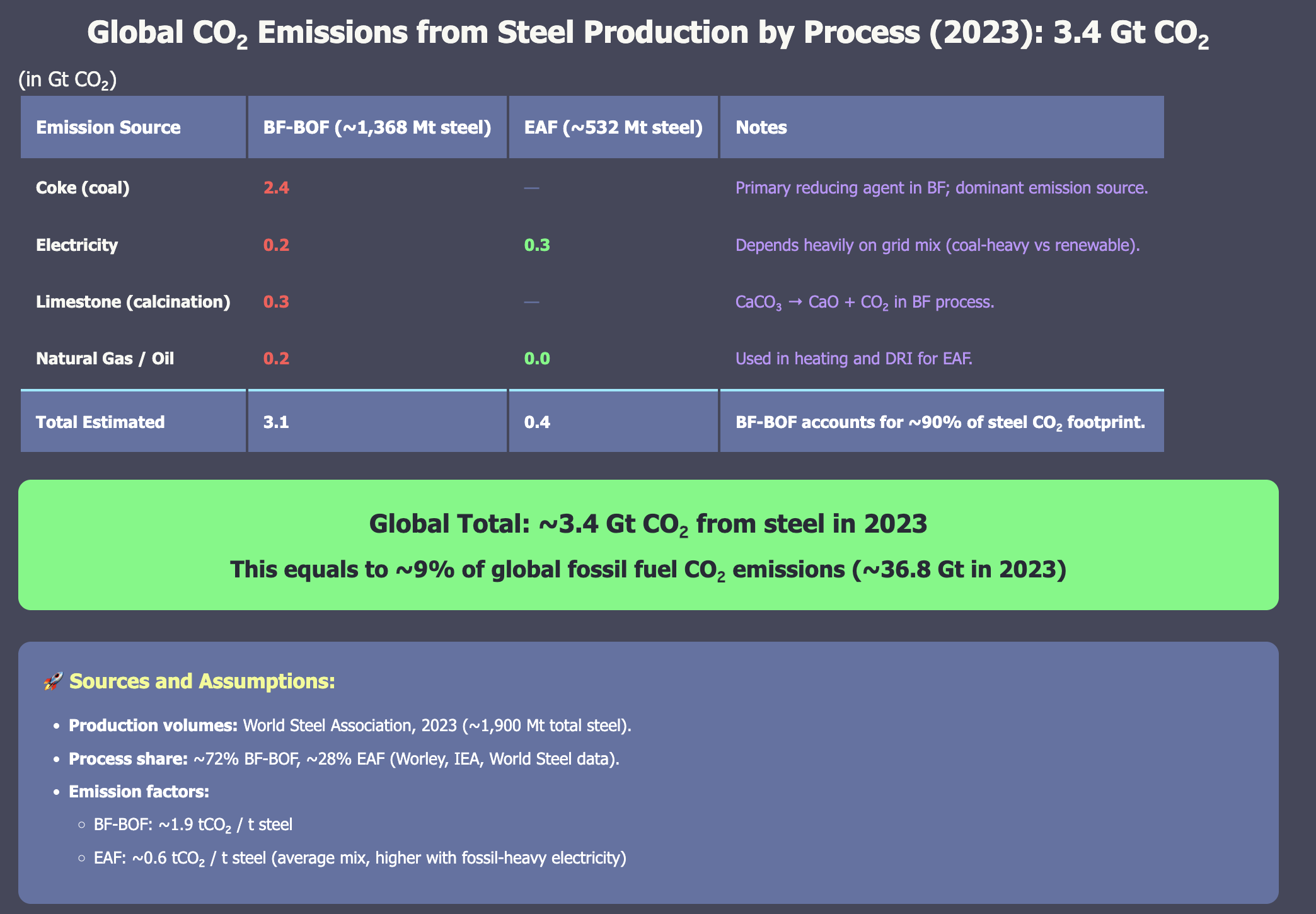

Globally steel making is responsible for something like 7-9% of total carbon emissions. Therefore decarbonisation must involve steel. A few years ago the opportunities to do so seemed limited and very expensive. And to some extent they still do but it maybe that there is a big role for Australia. One that involves our major iron ore producers working in partnership with Federal and State Governments.

I think it’s most unlikely that Australia will ever be the world’s major steel maker. But there just might be an intermediate role producing iron instead of iron ore. The total investment required would make nuclear look cheap and it’s probably a 50 year journey if it works at all. Lets start with the steel is a big share of global emissions.

The next step is to see that as an opportunity rather than a threat or a problem. Because we are so early in the decarbonisation journey it’s not yet clear what the most economic pathway is. Our biggest resources companies, BHP and RIO in concert with Bluescope and academics at ANU, University of Newcastle have looked at the basic research and developed an idea to the point of feasibility. Its no more than that.

To understand the ideaI had to go on the journey of how steel is made. Frankly it’s not that easy. When you see images or automated iron ore trucks and trains loading up big ships heading off to china where the ore is poured into a big pot and steel pops out it seems very simple. But I have found it isn’t. So this note will likely contain even more of the usual errors. Also I started this journey skeptical. I have long believed and still do in comparative advantage. We mine the ore, China makes the steel. But now we have a need and perhaps an opportunity to change.

Value adding pathways

The following figure is adapted from Jorrit Gosens presentation to Smart Energy. We interviewed Jorrit on EnergyInsiders but I should have done more background reading first. Still the SmartEnergy presentations were instrumental to me starting to read up. The figure shows various alternatives for decarbonising steel as you go down the table the amount of value adding in Australia increases.

The ESF (Electric Smelter Furnace) process

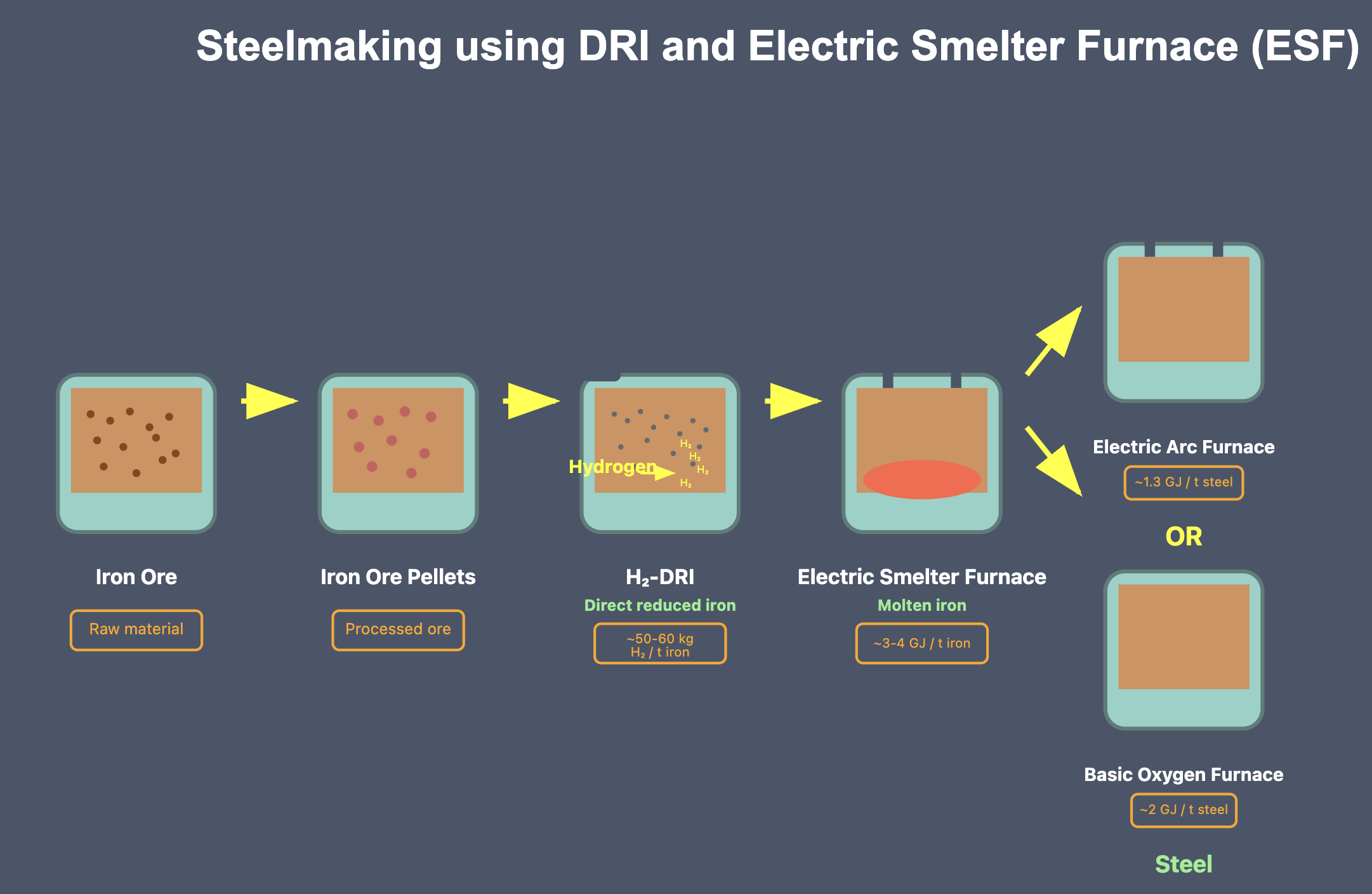

The following figure just shows that with the energy consumption added in. Based on my reading I believe that the DRI process requires pelletisation as shown in the following diagram and as allowed for in the cost calculator. However much is unclear.

Cost comparisons

I very much doubt that the numbers shown in this table are all that realistic. I have more background in thinking about the electricity cost for the electrolyser than anything else and the essential problem is that yes solar at $50/MWh is a plausible number at scale, A$30 is not impossible, you wont get 8000 hours a year of electrolyser operation from solar alone. So you need to believe solar and wind, let’s ignore firming can give you 8000 hours a year. If you like you can invoke using more hydrogen during solar hours to be stored and used at nighttime but that is likely to make the economics worse as hydrogen based generation is wasteful compared to solar generation and the highest value use of the hydrogen is for iron ore.

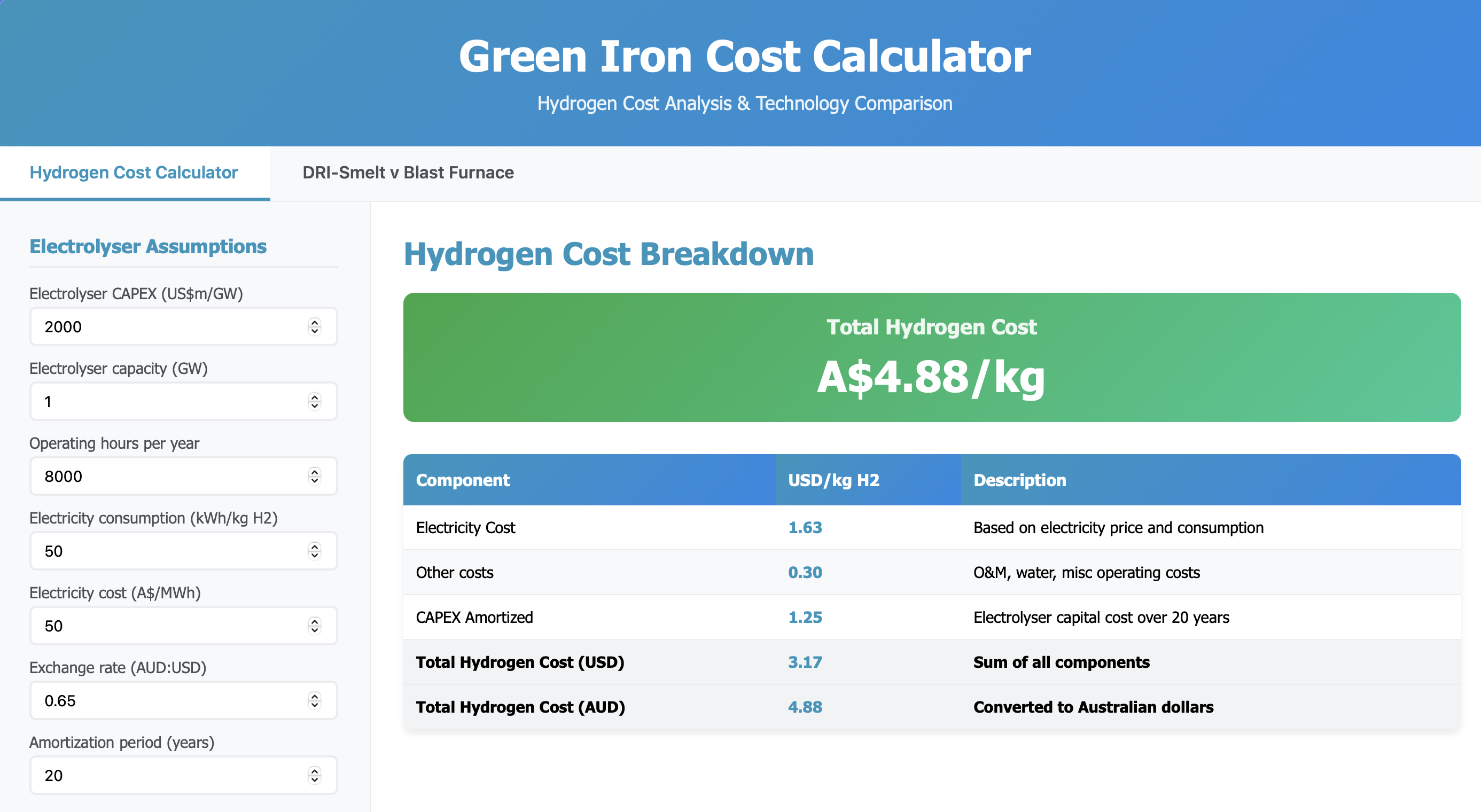

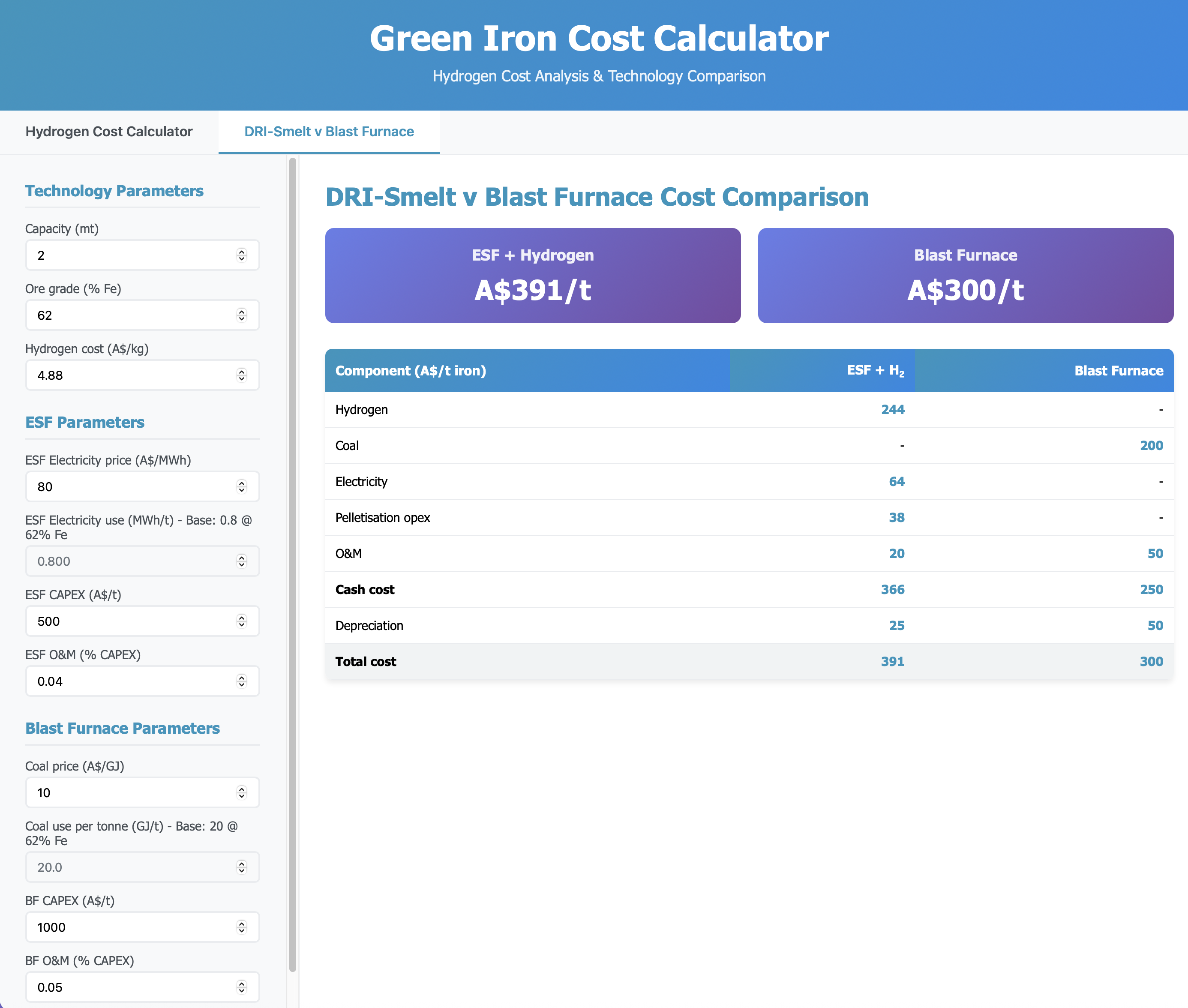

So I’ve put together a small calculator which lets you make your own assumptions. Here are a couple of screenshots of the default outcomes. The calculator can be found at ESF and hydrogen cost calculator along with some other introductory steel and iron ore material.

My assumptions make it seem plausible and encourage me to a “rosy” view no doubt it wont be that easy or anything like as easy. A carbon price of A/$90/t would be enough to make the ESF route cheaper than the traditional blast furnace. Assuming hydrogen at sub A$5/kg. It was only a couple of years ago we were talking about hydrogen at $1/kg but that was always hard to believe.

Grim reality: A$1 trillion (’000 billion) of capex + another A$1 trillion to make 2 PWh of electricity a year

It’s when I see the numbers in these tables that I’m inclined to put it in the too hard basket, and I would were it not for the need and the opportunity. Firstly the overall capex.

Then I calculated the electricity Capacity assuming 1/3 solar and 2/3 wind. Of course I know it’s not even remotely as simple as that, this was just a task sizing estimate and it comes to another $trillion.

I used an old number for wind on the assumption that if this program ever got going at reasonable scale then there would be project learning rates.

Disclaimer and HBI history:

I relied heavily on limited internet research together with some presenations from staff at the ANU to SmartEnergy in putting together this note. To be a steel analyst at an investment bank takes a couple of years of training. My cost estimates could well be optimistic, the smelter may not work. All the mistakes, and there are bound to be many, are my own.

An example of a previous attempt to add value in this space was BHP’s Boodarrie, Port Headland, HBI plant which I recall because its failure lead to some excess gas generation capacity in WA

In June 1995, BHP announced plans to construct Australia’s first direct reduction plant, aiming to convert iron ore fines into metallic iron briquettes using FINMET fluid bed technology. The primary goal was to add value to iron ore by producing HBI, a premium feedstock for electric arc furnaces, thereby targeting steelmakers in the Asia-Pacific region.

Operational Challenges

Despite the strategic intent, the Boodarie Iron plant faced numerous operational difficulties. Technical issues plagued the plant from the start, with persistent commissioning problems and technical challenges leading to significant cost overruns. Between 1998 and 2000, BHP wrote down the plant’s value by A$2.56 billion due to underperformance and escalating costs. Safety concerns also emerged when a fatal explosion occurred during maintenance in May 2004, resulting in one death and serious injuries to two others. Investigations attributed the incident to dust explosions, with hydrogen formation during cleaning processes identified as a contributing factor.

Outcome and Closure

Following the 2004 explosion, BHP suspended operations and placed the plant under care and maintenance. After evaluating options including partnerships, conversion, or sale, the company decided to permanently close the facility in August 2005. The closure incurred an additional US$266 million charge, and the plant was eventually demolished, marking one of the largest industrial demolitions in the Southern Hemisphere.

Key Problems Identified

The project faced several critical issues that led to its failure. The FINMET technology did not perform as expected at the required scale, representing a significant technological limitation. Economic factors including low production rates, declining iron ore prices, and high modification costs rendered the project economically unviable. The fatal incident also highlighted significant safety risks associated with the plant’s operations.